Mary Nomura

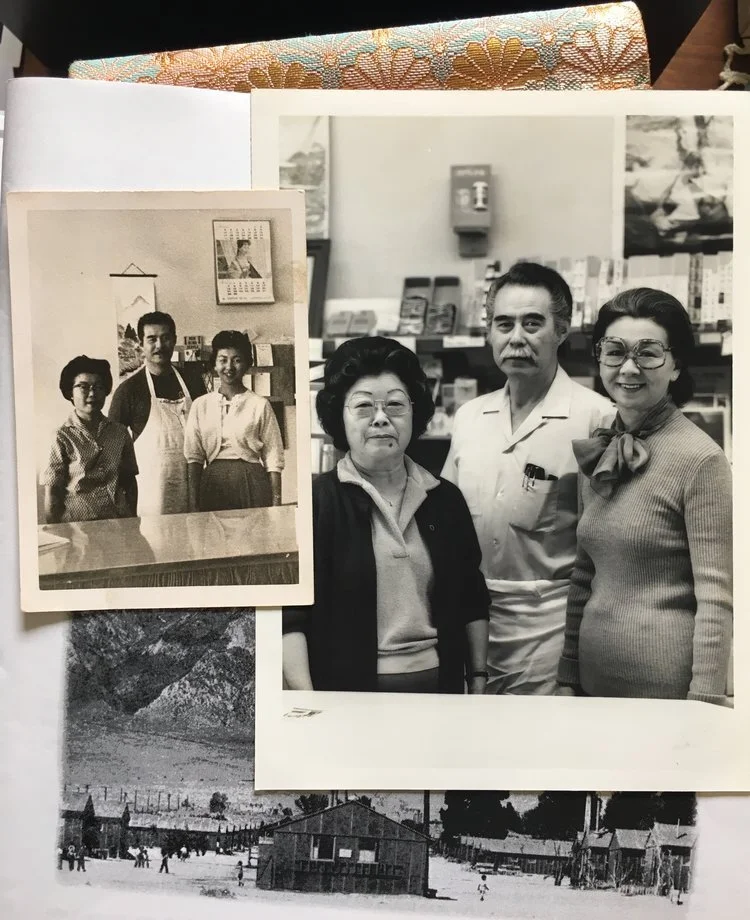

Mary behind the counter of her family business, Shi’s Fish Mart

““I always thought when I was a little girl, ‘I’m going to be a singer on the radio.’ I thought I would not get in the movies because who’s going to see a Japanese girl perform in the movies? So if they hear me singing on a record, they won’t know it’s my Japanese face singing.””

Mary Kageyama Nomura was a teenager when the war broke out between the U.S. and Japan. She and her siblings were living completely on their own in Venice, all orphaned when their parents died within four years of each other. This left the unexpected responsibility of providing for the family to her eldest brother, who quit school to go work. Although they were difficult times, Mary’s mother gave her a great gift before she passed: The love of music, singing, and performing. Mary’s mother would constantly encourage the children to spend any extra money, if they had it, on going to see shows and exploring music. “She always told my brother and sister, ‘If you even have a dime, save it and go see music. Go see plays, and always stick in the arts.’ She’s an Issei, you know?” Even today, Mary remains surprised at how her mother truly embraced the arts during the Depression – not to mention as a first generation migrant from Japan.

Later on when the war broke out and the family was incarcerated, Mary made the best of a bleak reality. It was her musical reputation that gave her the well-known moniker of “Songbird of Manzanar” and connect her to her future husband, Shi Nomura, who first saw Mary perform in a Nisei Week show in Los Angeles when she was just 14. But they wouldn’t meet until their paths crossed in camp years later, seemingly destined to be together: Shi fell for Mary instantly, and later looked back at the camp experience with nothing but fond memories, remembering it as the place he met the love of his life.

I wanted to start off with what a typical day was like for you before the war. And so I know you were a teenager, and what were your parents doing, and what was a day like for you?

Well, to tell you the truth, in 1933 is when my mother passed and so I had no mother from eight years old on, and I had no father from when I was four years old on. They both passed by the time I was four and eight and so my brother was the eldest of them, who was only 11 years old and quit high school and supported us. The Depression was nothing doing for anyone and he as a teenager had to find a job to support his sisters. He had two little sisters and one younger sister who was just a year and a half younger than he. And so they both quit high school and he found a job, he watered plants at a nursery as a teenager and brought a few dollars home to support us and my sister found a job in a produce market washing vegetables and things. You know they were only 17 and 16 so that was pretty hard.

So my mother, when she was thriving, she was a music teacher and so we always had music in the house because she loved it. She was a teacher of shamisen and odori and gidayu, joruri, they called it I think, and so I picked it up from there when I was a little girl.

Mary’s mother (center), her future step-father, and her students

I think when I was five years old I appeared on stage singing joruri and opera type thing with my mother, didn’t know I was learning that just by listening to her play and teaching her students. I was behind the door listening. I started copying her and she was surprised. So she put me on the stage, at a recital.

She must have thought you were good, that you could actually sing.

Well she never told me I was good but she put me on the stage.

Did your mother study music in Japan?

Yes we went to Japan in 1999 with all my brothers and sisters to look for mother and father’s family. We didn’t know anything about them. And so someone told us where they’re from. So we went to those two places in Japan and found out that she was just a little renegade. She would not go to school she would cut classes and go to the music school and just listen on the side and to try to learn how to play shamisen to sing and to dance. And so they went after her every day after school because she was a truant. And so they would bring her home and she would sneak away and do it again. They finally gave up and sent her to music school. So when she came over here was ready to teach, she was just a youngster when she came here. But was ready to teach.

Mary’s parents, Tomitaro and Machi Kageyama

Just driven, she just loved it.

She always told my brother and sister, if you even have a dime save it and go see music. Go see plays, and always stick in the arts like that. She’s an Issei, you know? She had that drive for her children, she says you got to keep on with music.

Yeah that’s unique. You don’t hear that push for the arts. What prefecture was your mother from?

My mother is from Chiba near Tokyo. And my father was from Okayama which was a pottery area, they made the bizen-yaki. My mother she was always, you know, doing something with students and she loved to go fishing, to go abalone picking, and she was like an all around kind of a person, she did everything. So I guess my sister and I kind of took after her. We would not sit at home and read books, we were always going about and around.

You wanted to be active. So do you remember the day that Pearl Harbor happened?

Yes. I was 16, almost 16 and a half. And we just heard on the radio because we had the Sunday radio on and we were shocked, we were just bewildered. Japan attacking a big country like this. I was just shocked and the neighbor on one side would shun us and just threw daggers at us and started calling us names right away. But the one across the street, they were Italians and they were the sweetest, nicest, kindest people and the daughter was my very best friend, and the son was my oldest brother’s best friend too. So they were always supportive. And in fact when I got married, I named one of my daughters after her.

Oh wow. So the parents obviously were sympathetic, good people.

Yes, she would bake the Italian breads and bring it over and make pasta bring it over. They were just really sweet, kind, honest people and they’re the only ones that I could really remember that were real kind to my brother, who is our guardian at that time. They would they put his car up on the block for him during the war time when we were incarcerated, kept it for him and ran it for him to keep it going. Just sweet, kind people. They were around, but we just didn’t see too many of them.

A Kageyama family portrait. Mary’s father Tomitaro is on the far left, her mother Machi is center, and her future stepfather is on the far right.

That’s true. Yeah there was just pockets. It wasn’t a popular thing to be kind.

No, you were not supported.

Was your neighborhood diverse? Was it Japanese?

No Japanese, we were the only Japanese except for behind us there was a ranch, a farmer’s ranch, and they were very good to us because we had no parents and so they said just help yourself to what was out in the yard, free, out in the field and take what you want.

How sweet, and where were you living?

Venice.

And so you kind of saw this backlash, some of this backlash towards you and your family.

Oh yes, in school especially. One teacher before the evacuation order went out she says, “When you’re going, when you’re leaving?” She was very crude and I just had to keep my head down and say “I don’t know,” because I really didn’t know, I was quite naive. I had no idea what was happening, what was going to happen to us. My brother took it all in and he would never let us know. I don’t know, he was trying to keep it from us or he didn’t want to or he just felt so ashamed or sad that this was going to happen to us. He knew nothing about what was going to eventually be our fate. He just knew that we had to leave so we didn’t own our home. We had a rental and then we had no money we were very poor so we couldn’t buy suitcases.

So my sister, the eldest, she was already married by then. She was, she got married at 19 years old, 1937, and she went out and bought heavy canvas and sewed duffel bags for us and we took all of our belongings in duffel bags. I remember it was a striped canvas. We just took our clothing. There’s nothing else we could take. So my mother’s instruments and she even did some barbering on the side, her barbering things were put into the Japanese school, and they stored it for us. Then we found out that a lot of people broke into it or the person who was supposed to be guarding it were letting people come in, so a lot of the things were lost. Some of the things my brother was able to recover but not some of our precious things.

Was your mother’s instruments there, or some of them?

She had shamisen and we had the piano, beautiful piano. She played all kinds of instruments and she just learned all on her own she never took lessons. She could play violin, the piano, shakuhachi and the drum and the shamisen. Yes she just knew how to do it. I never saw it, my sister told me a master shamisen instructor came from Japan to test her and he played the tsugaru, a real fast one and she kept up with him. He was surprised and she had no lessons. But she could keep up with him because she had that in her mind that she could do it. So anyhow, I understand she was quite talented but I didn’t even hear it, because this was before my time and I was too busy playing outside, maybe.

And so your brother, as a surrogate parent at his young age and he knew you had to leave, what was that conversation and do you remember what he said?

Like I said I was very naive and I said, “Oh we’re going to go someplace? Oh goodie!” You know we were poor – we got to go see movies and go to the ocean, go to the funhouse house and all that, that was our going places. When they said we’re going to take a bus and go someplace, I said “yay.” I was dumb and 16 years old. My little sister and I went thinking we were going to go to a camp. You know, so when we got there, what a shocker it was, but that’s how my brother prepared us, we have to leave everything. We can only take this. We have to leave and we don’t know when we’re going to come back. That was what he told us and he never told us it was done because the government said we had to leave the Pacific coast, he never told us that.

When did you find out that it was a government order?

Along the way there, we said ,“Where are we going?” And he says “We’re going to a place where we have to stay where we don’t know how long we’re going to stay but we don’t know where it’s going to be either.” It was a shock to see the vast area of black tar papers. We were shocked. That’s what we’re going to live in? You know, and I thought, “How long? What’s going on?” We were all just bewildered. I cried that night because I had no idea what was happening to us. We had no future that we could count on, that it was done for us. We stayed there until they told us we couldn’t, because we didn’t have to or something. But I didn’t even think ahead of that, about what’s going to happen after we get out of here.

When did you know it was all Japanese Americans?

That was a shocker.

That was a shock to you as well?

Yes, because being where I was it was a community of Japanese farmers, we never associated with them because they were different. I mean they were squares, and we were crazy, you know, we were really nuts and crazy about doing things that Japanese parents would frown on. Roller skating, and running around in the pasture and gathering mushrooms and things like that. Those kids never did that, they went to Japanese school and they were nice little girls. So that was not good for me not to be able to associate until I went to camp, then I made some wonderful friends and we’re still friends to this day. We still get together. We made a club called The Modernaires in camp and they were all my age. It was fun.

So when you got into camp and you started making friends, how did the singing come along? How did you become the one that was asked to sing?

Before the war they used to have the Nisei Week talent shows. I as a 13 year old and a 14 year old, I went with my brother because he liked to sing and he loved music, and so I tried that and I was asked to sing with a talent show. Two years in a row I sang in that Nisei Week talent show. So by the time I went to camp when I was 16 they knew that I used to sing. Then they asked me to sing. One of the first functions I sang at was when they were introducing the Japanese faculty with the Caucasian administration and they asked me to sing, no accompaniment. And I got up and sang and then I sang “Tangerine.” At that time it was a song that was popular and then next time they had another get together I just sang with the piano and the music teacher used to accompany me.

Were you still practicing or taking any kind of lessons?

I took lessons when I was 12 years old until I was 15, 16 almost. The reason I got to take singing lessons at a time when my brother could barely afford to put food on the table is that he bribed me not to go to Japan with my little sister with my step father. My mother remarried right after my father died because she had so many children and so right after, I’m sure within a year or so she remarried. And so he had a child with my mother, and he wanted to go back to Japan to start life anew because he didn’t want to have this millstone around his neck of having so many kids. So he took his son but he said he’d take my little sister and I, Mary, with him, maybe as a token expression to try to make it easier for my brother to support us. So my brother says, “No, I don’t want them to be separated,” so he said “If you don’t go and you stay I’ll send you to singing school.” Okay, I’m staying! It costs 50 cents for him to send me to singing school. 50 cents. That was a big deal for him to put that money out because he used to put a dollar on the table for my sister to go shopping to buy food for us.

It went a long way back then.

Yeah it did. Yeah to buy bread, meat, milk and all that for school.

So that’s an amazing that he knew that, that for you was enough.

Oh yes, he knew that’s what I wanted.

So you were closer with your brother.

Yes, so I named my first son after him.

What is his name?

Akira, Frank. Akira so I named my son Alan Akira, none of my children have Japanese names but he’s the only one I gave a Japanese name to.

When did your brother pass? Was he around for quite a while?

Yes. He died in 2012.

He really lived a long time.

1916 he was born.

Going back into Manzanar again, was there one person that gave you that nickname “the songbird”?

I don’t know who gave me that nickname, but I kind of think it could have been the music director of the camp, Louie Frizzell. He took me under his wing and he used to go out into the camp on the days when he didn’t have to teach and bring brand new sheet music for me to learn; new songs of the day, the current songs. You know things like Judy Garland or Doris Day or whoever was popular and he would bring back new sheet music for me to learn and teach it to me and accompany me in all programs we had at camp. So I always considered him my mentor, he kept me current.

He’s like, here are the contemporary songs.

Yeah I could sing contemporary songs. “Meet Me in St. Louis” by Judy Garland and things like that.

What were some of your favorite songs to sing? Are there any that you think of that define that time for you?

The up tempo ones that I really like to sing are “Accentuate the Positive.” “Night and Day” and “Old Black Magic.”

When you were in Manzanar what was your state of mind? I mean eventually you there for three almost four years. First it was a shock but then you started making friends. At what point did you feel did you get into some kind of groove?

It was early that I could get into it because it was in April when we were put it in camp in school I was in 11th grade. So I had to go to school and I’ve met so many Japanese, I never knew that there were that many Japanese in the world. So I mean we were best friends right away. And so this time in my life I was beginning to meet people I became lifelong friends with. And I was shy, I didn’t know anything about boys. They meant nothing to me and I just had lots of fun with the girls and played softball with them. Then I started dating with the high school classmates and stuff. Then I got very, um not involved, but he was my best boyfriend and we were going out for quite a while. We had just graduated high school and then he had to go to Crystal City to join his father. So we separated and we kept corresponding back and forth. It was kind of futile because we didn’t know what was going to happen to us. And so I had to give him a Dear John letter. In the meantime I was still entertaining at the camp and the camp programs.

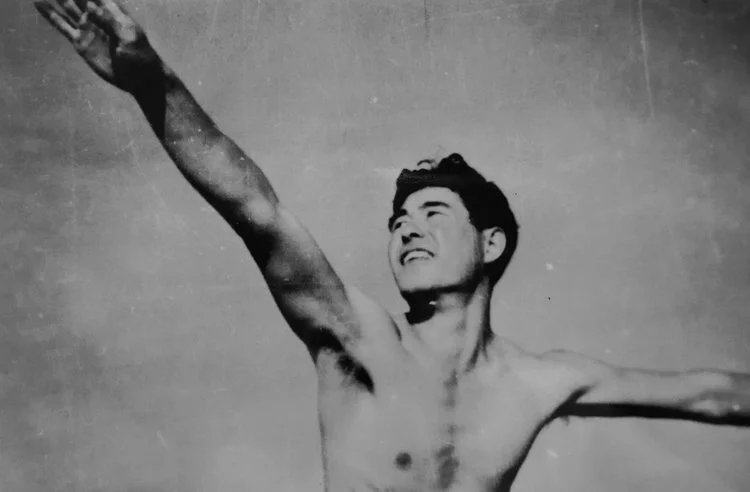

Shi Nomura

I was asked to sing for the group called the Manzanites, one of the better men’s club in camp with all the good looking men, all the sports guys were in it. They were having their dance and they asked me to entertain. So in those days they always have an intermission to have somebody tap dance or sing. And so the adviser of that club was Shi Nomura and he says, “Does Mary have an escort?”

And in that camp everybody knew who was going around with who, who broke up, who’s getting married all that stuff. They said “No her current boyfriend had to leave camp and there’s another boyfriend after the fellow went to Texas.” He just left for the East Coast to look for a job and we weren’t really, we were separate just dating. He says “Then one of you boys take her.” And they said, “Well we all have dates already.” He said “Well then you boys who don’t have a date, you ask her. You take her so she doesn’t go to a dance by herself that night.” So the guy says, “She’s too tall for us.” I was considered tall in those days. He says, “Well I don’t want that girl coming and singing at night without an escort. I’ll take her this time but next time you make sure that she has somebody to bring her.” His friend came to the office where I was working. He says, “Shi Nomura is going to come pick you up because he doesn’t want you to come by yourself. And so I said, “Oh okay” and so he came to pick me up and I think that was in November, end of November. It was called a turkey trot, it was a camp dance and by New Year’s Eve we were spoken for each other.

Was that first time you met each other? When he came to pick you up?

He had seen me entertain pre-war days at that Nisei Week talent show. I said “You are a fickle man” because he was with his girlfriend sitting next to him, who he was going to get married to — that’s another long story. He heard me singing, and I was 14 and he says he was smitten. He says, “I’m going to marry that girl.” What an idiot, with his girlfriend next to him. That’s what he said he always remembers saying, “I’m going to marry that girl.” Then heard me singing in camp. He says “That sounds familiar.” He didn’t know me and so then when he took me–

He remembered you by that point, like he knew that was the same person from before.

I said you are a two timing, fast worker.

See and everything worked out how it was supposed to. When you went to dance with him or you were escorted, how was your feeling towards him at the time?

I really didn’t have that romantic feeling towards him but I said, “Oh he’s one of the more handsome — he was one of the handsomest guys in camp.” Very handsome man. It was nice. He was a gentleman and he was very cordial. We had a nice time and he asked me to a New Year’s Eve dance and then I’d never been to New Year’s Eve dance. Then my sister had a bunch of friends that were dating. My sister was three years younger than I, my little sister. And she says “I heard that he kissed you.” I said, “Yeah.”

Mary and Shi on their wedding day

So that was New Years and he says, “I want to get married and we’re going to get married. We’re going to tell your brother that we’re going to get married. He better agree to it because I’m going to.” I left camp in January. He was still in camp. I went to Pasadena.

This is because of your brother’s job?

Yes. California was opened up for the Japanese to come back so he got a job and I found a job as a housekeeper. While he [Shi] was in camp I made a recording. He’s used to write me love poems, used to write poetry. And I used to set it to music and I took those words and I set it to my own music and took it to a place to get recorded on one of those little records with the big holes in it. I sent it back to him. And so he had that record. And before I left camp, I made a recording with the music teacher on a big 78 disc of I think five of these songs that I recorded. So I think that’s the only recording of an actual music taken in camp of all the ten camps.

Is it true that your husband said, because this is where I met my wife, Manzanar was kind of a — I don’t know if happy is the right word?

That’s how he always said, that Manzanar was a terrible, terrible experience for everybody and a memory that they won’t forget, but I have to keep the other part the memory of my getting married and meeting my future wife there and having children after that and doing all the dedicated work at the museum. He says “I can only think of the better part of that. I can’t harbor the bad part of that because other people can do it, but I’m not.”

He wants to remember the good?

Yes, yes.

When he passed, again I don’t know if Alan [Mary’s son] said this, but did he say your husband say he wanted to be buried out there?

There was no barracks or anything there at the camp, he wanted to construct a barrack replica and make it a home for he and I to live in so he could conduct tours for anyone who came to see the camp to see what it was like. He says, “I want to live there and show people.” Just not me. I’m not going to live away from my children, and my grandchildren were about to come at that time. I said I’m not going to do that. But we did buy property in Independence so we could retire there. There was a three plot mobile home area of what I guess you call a mobile home. The one facing the mountain was the one he bought and we were going to retire there someday. I said well we can go back and forth but I’m not going to live in the barrack. So we did buy it, but he passed. He was still doing work with the museum [in the town of Independence]. So they still call it the Manzanar Project with Shiro Nomura. He said, “If it wasn’t for this, we wouldn’t have met at all”. He lived in L.A. I lived in Venice. We would not have met. So he always said that was a plus, the only thing he could say, it was a plus. And then after that we just went here and there and had kids in between. Five kids. And when I came out of camp I was a housewife, and the only time I went to work was after my children were all born and we started a fish market. We had a fish market for 22 years. Popular and quite successful.

Did anyone take it over after you?

Nobody wanted it except my son-in-law who is Jewish. Nobody wanted the hard work. We kept it so clean and people would come in and go, “How come this doesn’t smell like a fish market?” Because we scrubbed down the floor and everything every night.

What was the name of the fish market?

Shi’s Fish Mart.

The Shi’s Fish Mart family when it opened (left) and when it closed (right)

Of course it was!

So people would say “Shish Fish.” But then within the last eleven years of his life he developed Alzheimer’s and he forgot a lot of things, he forgot how to say things, even the mid part of it he says, “What’s your name?” to me. He could not remember. He could not remember how to eat, how to pick up utensils to eat. He completely lost all modes of existing.

Thinking about this time right now in this kind of political climate, are you afraid and surprised you’re seeing similar things?

I don’t think the government, the Congress is going to allow it. They will not allow it. I’m hoping so, but I’m pretty sure they won’t allow it. But that big guy is adamant about making that happen because he is so bent on having that wall built. I don’t know what your political affiliation is but I just don’t go for it. But I don’t think Congress will allow it to happen because too many people are so against it in America.

That’s true and the Japanese Americans fought too hard for it. When you received the redress money what was your feeling when you got it? Did it mean something to you or what did that mean to you when you got the apology?

To me, it wasn’t enough. It was a token gesture. It was something that was misused. You know “arigatai,” you know we thought, well that was something. It was a token but how can you put monetary value on what they did to all of us you know? I’m not saying we should have gotten more but it just wasn’t, it wasn’t the right way or the right way to say it for what they did. It just wasn’t right. It didn’t settle my feeling that that’s not enough. Not enough not in a monetary way, but how can you forgive that? So many lives were affected by that. People, mentally and physically and I just I felt that it was okay for some people who really needed that money even because it wasn’t enough. What I thought wasn’t, it was just a token. And I can’t say it should have been three times that amount. But I can’t put the monetary value of that in all of that but I just didn’t settle so because “Oh great I don’t buy me a car” and just flip it because they’re doing OK. You know there’s some people just struggled and the majority of it got all over it. We did alright. I mean it’s just something that says we’re not down on the ground having people step on us we were just able to get back on our feet and do things, but it’s just the thought of it should not have happened, and what they did for us afterwards thinking this is going to be our token apology. It wasn’t. No it wasn’t.

Did it affect your oldest brother in any way?

I shouldn’t say the word blessing, but it was a blessing for my brother. He didn’t have to struggle to take care of his three little sisters. He didn’t have to go out and look for money, to get money to feed them, and pay for rent and all that. So the government took us and made sure that we had so-called roof over our head and fed us it took that responsibility off of him. And so my sisters and I felt that it was a blessing for him. It made it easier for his life until he met his wife in camp also. So from then on it was easier for him. We don’t know how it would happen, how would we have survived with welfare or whatever to take care of us? In those days it was, “Oh no, Japanese people don’t use things like that.” But it was pride that allowed him to take care of us but I don’t know how he would have kept it up.

Well then it’s something again positive, that helped.

Yeah that’s the way we look at it, it helped my brother. He didn’t have to struggle to put food on the table and take care of us.

I understand that you didn’t pursue singing professionally?

I never did. I just sang when I got asked to sing at programs, because I always thought when I was a little girl, I’m going to be a singer on the radio. I always thought I would not get in the movies, because who’s going to see a Japanese girl performing in the movies? So if they hear me singing on a record, they won’t know it’s my Japanese face singing. So I always thought, well I’m going to be a singer and make recordings. That’s what I thought I was going to do.

The fact that you didn’t but you still kept performing, I’m sure you just feel happy that you could still sing in any kind of context.

If somebody asked me to sing, I said, “Well let me know early enough so I can practice.”

Originally published on Tessaku by Diana Tsuchida. Read more stories here