Digger Sasaki

Agnes and Digger Sasaki at the Oakland Buddhist Church

““They had soldiers and jeeps with machine guns, you know, patrolling the camps. It was kind of exciting in a way.””

Dick Sasaki has a peculiar moniker, one that has fully replaced his given name and dates back to high school. “In high school, I played football. And you know when you practice, you have to push a sled to strengthen your legs. When people push, everybody says, “dig, dig, dig,” you know. And then one day the coach said to everybody, “Dick here is the smallest fella on the team, but I think he’s the best digger.” So ever since then it stuck with me since high school days.

Digger sat with me for an afternoon at the Oakland Buddhist Church, as his wife Agnes assisted with the interview and filled in details to his stories. His standout memories of camp were of teenagers playing, dodging the army trucks, trapping rattlesnakes outside of the camp.

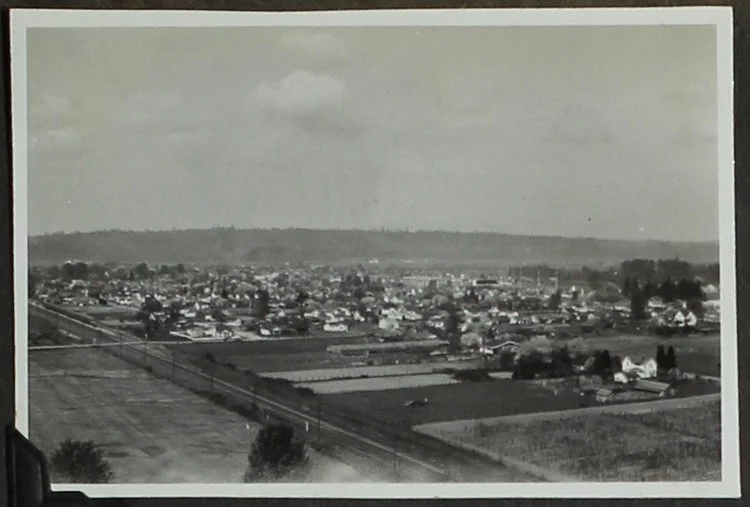

A view of Auburn, Washington in 1946. Photo: Masao Sakagami Collection

Tell me a bit about your childhood and where you grew up.

Where I was born and raised until I was seven, is a small place called Enumclaw, Washington. And that’s about 20 miles east of Auburn. And it’s on the way to Rainier Mountain. They had this Japanese community there and there was a sawmill and a pond, actually all these Japanese worked at the sawmill and some worked building railroad tracks so they could bring the lumber from the forest to the sawmill. Roughly there was maybe about eight families there and then they had a separate barracks for bachelors. I remember growing up there until I was seven.

Because your father was working in the sawmill?

Yes, right. He worked at the sawmill. And my mother, she was the cook for all the bachelors that were there. So she had to get up real early in the morning, and cook and feed these bachelors. So I felt neglected. [laughs] No, no.

So you lived there for how long?

Well let’s see. I remember at the pond, a lot of the older kids would swim to the logs and stuff. And some of the younger kids would climb on the backs of the older kids and get a ride to the log and back. And one time I got on this fellow’s back and for some reason he just couldn’t make it any further I guess, so I fell off and I could see the bubbles going up. The next thing I knew they were rolling me over a barrel, because I had so much water.

Agnes Sasaki: Yeah, so you almost drowned.

DS: Yeah so, I remember that part of it anyway. And at that camp there weren’t too many young people my age. Maybe there were two others, about my age. Then once I turned seven we moved to Auburn, Washington.

And was it because of jobs changing?

Well, my grandparents had a laundry in Auburn but they got too old. So my mother went to run the laundry then once she started, the parents passed away so she was running the laundry by herself. And my father still worked at the sawmill so they were parted during the week. So from seven years old ‘til I went to camp, we spent that time in Auburn.

Do you remember having a fairly comfortable childhood?

We weren’t rich, that’s for sure. My mom had to work hard and so did my dad, too, so. They managed.

Were they born in the United States?

No, they’re both from Hiroshima.

Do you remember the day you heard about Pearl Harbor? Do you remember what the feeling was like?

Yeah, December 7th. It was the big news on the papers. In fact, I was helping my Caucasian friend sell papers on the street. It really didn’t hit me as bad, you know, I just knew that Pearl Harbor was bombed but that connection with Japanese really didn’t hit me.

Do you remember if your parents were worried or thinking something could happen?

Well, they were worried because of the discrimination. Because it was bad enough as it was before the war so with the war starting, you know, they were more concerned.

Do you remember anything specific that happened?

Well, a lot of times they would call them “Japs” and so forth, yeah. Their English wasn’t that good, so a lot of times they won’t understand what the Caucasian people were saying. I remember the FBI coming to the house and store and checking everything out. They confiscated certain items and in fact, they even took my toy samurai sword.

I’m sure you were pretty upset about that.

Yeah, oh yeah.

That’s traumatizing, to have people come in and raid your house.

Yeah. But as far as school, I didn’t really feel any discrimination at that time. But like at school when we had lunch, all the Japanese fellows would eat together, so. But a lot of my caucasian friends didn’t seem to bother me because of the war at that time. I guess it was just too early to realize what’s taking place. Plus we were young, you know. I was 11 years old when I left Auburn. When we had to relocate we had to go to Pinedale Assembly Center. One thing kind of did touch my heart is when we left Auburn, we boarded a train. And my teacher brought the class to send me off. So, that was really nice.

Were you the only Japanese in the class?

Yes, right.

Agnes: Now I remember that because when we went on the first Tule Lake pilgrimage, he had never told me this and the bus people were just talking. I forgot about that, that was so touching.

Digger: And I corresponded for a little while [with the teacher]. I sent one first because she didn’t know my address or anything. But eventually I quit writing. I remember her name was Miss Louis.

It probably was before people picked up from their parents the prejudice. Do you remember the conversation that your parents had with you about relocating?

There’s that word in Japanese, shikata ga nai. So we more or less followed the crowd, you might say. They didn’t seem to talk that much about it.

They just said, ‘You need to pack and we’re going?’

Yeah, because I don’t think they knew themselves. All we knew is we’re supposed to report to a certain spot and we had to take whatever we could carry. And before that, we had to sell whatever things because we couldn’t take to camp. I remember selling my bicycle for just pennies just to be able to get rid of it. And we had our car, we just more or less had to give it away.

So then you were taken to Pinedale. What was your first impression of arriving there?

Well, once we got on a train, all the curtains are pulled down so you couldn’t see out. And I can’t remember exactly how many days it took to get to Pinedale. I remember on the train they just had chairs, nothing to sleep on. So, every once in a while they’ll stop, way out on the desert or something so we could get out and stretch out and get back in the train. But we had no idea where we were or where we were going. And you get back on the train, and train takes off. Eventually we got into Fresno area and from the train station they put us on some trucks to take us to Pinedale.

And how long were you in Pinedale?

Three months. We got there in May. And you know, living in Washington in our area, the climate is nice and on the cooler side. So once we got to Pinedale and Fresno area, it was really hot. And that’s the first thing my parents complained about because we get there and they assigned us to a certain barrack to stay in and they issue mattress covers. It’s just a bag, and then we had to fill that with hay.

You had to do that yourself.

Yeah. And then they had a steel cot. And nighttime comes. You go to sleep then wake up in the morning and the bed’s about that much into the ground because of the heat and the weight. It was an asphalt floor. The bed actually sank down into the ground.

Do you remember how your parents tried to make you comfortable or make it a home?

Not really, yeah. Like I said, they just more or less lived with it.

[To Agnes]: And where were you?

My dad had a farm in Gilroy. But then they thought that if you went to Reedley, we wouldn’t be sent to camp, so we went there. Reedley is near Fresno. But then from there, we were sent to camp. Everybody thought that you went to an assembly center first, but I don’t remember that. From what I remember we went from Reedley, straight to Poston, Arizona. And then, I guess some of our family, my mom’s side of the family also must’ve come to Reedley because we were all in Poston together.

How old were you?

I was three. I was three, four and five. So I thought it was fun, I thought we were moving. I had no clue what was going on. But as far as I remember, from what my parents said, we don’t recall an assembly center. And then when we came out of camp, my dad lost his farm in Gilroy. I forget if he sold it cheap or somebody just took it or whatever. So we had no place to go back to in Gilroy. And the reason we went back to Reedley, was because his older sister and her husband, their Armenian neighbors, kept their farm for them and worked the farm. So we went from camp to Reedley, lived with them until my mom and dad found a house in Reedley. He became a custodian in an elementary school. So he never did go back to farming.

And what else did your parents do?

On the side he worked at a manufacturing company, Salwasser but that was kind of on the side, he was mainly a custodian. My mom, she was an office receptionist for a doctor. Then I forget if she worked in the hospital for a while.

Did they ever talk about camp?

They were Nisei, his parents [Digger] were Issei. But even the Nisei, that generation, really didn’t say much. I don’t know why our parents didn’t talk about it. Whether it was cultural, I never thought of it. And like I said, moving it was fun. And when I got out, I don’t recall any discrimination or anything and we were back in Reedley, at a country school. But I don’t recall being discriminated against or something.

[To Digger] I think it’d be interesting to talk about your first impressions of Tule Lake.

Being in Pinedale for three months, it gave me a little awareness of barracks and stuff. But Pinedale was so small in comparison. And the reason they sent us to Pinedale is Tule Lake wasn’t finished as far as building all the barracks. To tell you the truth, I couldn’t remember how we got to Tule Lake from Pinedale. I was really impressed with so many barracks. Eventually I found out that that was the largest of all the concentration camps. I think they had approximately 10,000 people there. I was impressed with the size of the place. All the guards, real tall fences, you know. And all the guard towers.

Was that frightening to you at all?

You know, it must’ve been because of my age that I didn’t feel frightened or anything but everything was a different world. I don’t remember being scared. I was impressed with how large it was. And two landmarks, Castle Rock and Abalone Mountain.

Digger at the Oakland Buddhist Church

Were a lot of your friends there in Tule Lake?

It seemed like Auburn people were kind of in the same ward. There were six wards together and we’re in Block 49, like your grandparents. In our ward, there were a lot of the Auburn people but come to think of it, I just had a few friends in that ward. We would just play sports and just to keep busy I guess, sports was our main outlet or activity. And played basketball, baseball, and football without pads. And we tackled, you know. Then we had the segregation, that questionnaire. Number 27 and 28. Some people went from Tule to another camp. Because they went yes-yes. So they sent them to other camps.

Agnes: But your dad could’ve gone to another camp but he didn’t want to move again. Because Pinedale was the first move.

But did he believe in what he was saying no-no to?

I think he had his loyalty to America, yeah. I guess just staying there felt more secure for him instead of moving someplace else. That’s the way a lot of the Issei are, I think. They don’t want to venture out that much.

Agnes too Digger: Was he ever given the option of going back to Japan?

No.

And they wanted to stay in the U.S. right? Was the goal to move back to Washington?

I’m really not sure about that. I guess he would’ve moved back to Washington if anything. That’s the way Isseis were, they aren’t like the Niseis. They’re kind of settled in their own way, you know. Don’t want to try different things.

Do you remember observing any of that conflict in Tule Lake between the Issei and the Nisei? Or seeing arguments?

Oh yeah. I saw some fights and stuff between loyal and disloyal people. And there was a group of some I guess you call them Kibei, those loyal Kibei used to go to certain barracks and pull the occupants out and fight them and stuff like that. I remember actually seeing that.

And they were how old?

I would say early to mid-twenties.

And they would target people who said that they were loyal to the U.S.?

Yeah. Or they felt like they were spying on the disloyal people and stuff. I saw that incident and in fact I still know the person’s name. But I won’t say the name or anything.

Agnes: So another name for the disloyal were the no-no?

Yeah. You couldn’t really say disloyal, because some of them objected just because their rights were taken away. Well the government shouldn’t put out a question like that anyway, you know. That’s for women and men. If you’re at another camp and you said no-no, you went to Tule Lake. The question was for everybody.

It wasn’t the smartest thing but it was also brilliant, to keep all the resistors together. Did you see mainly Kibei doing that to the “loyals,” or was it a group of all different people?

Yeah, the group that I knew of was a complete mixture. There were a lot of people accusing different people for ratting on them. It wasn’t a good atmosphere in the camp because of that. That was before the segregation took place.

Did you see that mentality trickle down to the teenagers and younger kids or was it mostly just adults?

I think it was basically just adults, yeah. But once the segregation took place, even myself, we ended up having to go to Japanese school instead of English school. It was funny because some of the little kids knew more Japanese than we did. But we were towering over them.

A replica of a Tule Lake guard tower

So were you in the school where they had to wear the hachimakis?

I don’t remember how we ended up in that group. Maybe just to be active, I guess. In fact my friend [Ken Harada] and I, since everybody else were going, we joined it. Wore our headbands and we used to run around the camp. When you run, they used to say “Wasshoi, wasshoi,” so we were called the Wasshoi Group.

But after the segregation, my friend and I joined a so-called gang. Because you kind of had to protect yourself—they had other gangs within the camp. We used to make knives and things.

How many people were in this gang?

In our gang there were about eight. Ken and I everyday just stuck together. They moved in from Topaz to Tule Lake and they lived in the next barrack.

So this gang was more just to have protection?

Fortunately the other gangs, somebody knew somebody from the other gangs. So we didn’t end up getting into a big fight.

And these were all groups of teenagers?

I was only about 14. In fact before the segregation, I lied about my age and got a job at the warehouse and there were two older fellows. We were all in a truck and made deliveries throughout the camp.

So looking back at it now, you never saw camp as a bad or traumatic experience did you?

Not really. Another funny story is before segregation, there were four of us that we were able to go out of camp to go to Abalone Mountain. We’d go hunting for rattlesnakes and we’d get on the big rocks with the wire. We’d drag the rattlesnakes down and then we’d tie it noose-like, the snake, and put it into a jar. Then we’d sell it to an old person in camp. Then when we’d go see him, it’s in a jar, like it’s pickled or something. I don’t know what he does with it. He’d use it for medicinal purpose. One time we had a jar, I think we had two jars, and we were coming back to camp and this younger boy accidentally hit the rock with the jar and it broke and the snake got out.

What was your favorite memory with Ken in camp?

Well, when you look back, that gang thing was funny.

Agnes: Because it wasn’t a real gang.

Well, it was a real gang! Kenny and I, we were involved in a lot of sports. Baseball, softball, football, basketball. Majority was basketball. The courts were all just dirt. And then we built our own baskets, the supports and stuff. Yeah our gang, we called it hachimaru: Hachi is eight, and maru is round, so it’s for “eight ball.”

That’s clever.

We used to have jackets, the warehouse people used to wear. Denim. And somebody put it on our back, hachimaru.

You don’t still have that, do you?

[Laughs] No, I wish. But I remember when they had all these fights and riots, they had a curfew after. And Kenny and myself, we used to meet at a certain barrack, for gang activities. And then once the curfew came, after seven o’clock or so, you’re not supposed to be outside. But Kenny and I, they used to have jeeps that patrolled all over. We would go to the gang thing I guess past the curfew, so we’re dodging the jeeps. Getting home. It used to be kind of fun. They had soldiers and jeeps with machine guns, you know, patrolling the camps. It was kind of exciting in a way.

Originally published on Tessaku by Diana Tsuchida. Read more stories here