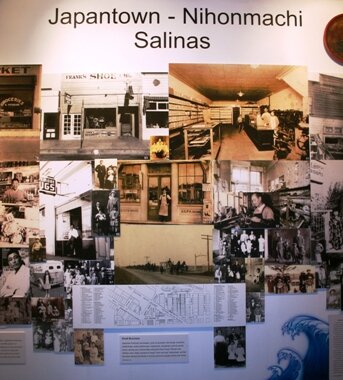

Connie Young Yu and Leslie Masunaga are JAMsj guest curators. They are currently working on the new JAMsj exhibit, "Common Ground: Chinatown and Japantown, San Jose," which will open in September of 2012. They sat down with interviewer, Nancy Yang, to discuss their vision for the exhibit.What inspired you to create this exhibit? Was there anything in your own life experience that drove you to create the exhibit? Connie: I grew up hearing about my parents and their oral history. My father was born on Cleveland Avenue (in Heinlenville, which no longer exists. Heinlenville was a Chinatown that would be located within the boundaries of present day San Jose Japantown). He was in his twenties when he left the 6th street settlement. My father was actually there until 1937. So his memories were very strong.He remembered Japantown and having Japanese neighbors. He saw the transformation from Chinatown to Japantown. This is what I think is really exciting. I feel that this site of Cleveland Avenue, of Sixth Street, and Jackson Street was the birthplace of the first Asian American community in Santa Clara Valley. It was no longer just Chinatown, and no longer just Japantown. More Asians moved in including Filipinos. This was really the first multicultural place.I think that the story (about Chinatown and Japantown) is very inspiring. You want to reach people in a way that they can understand and identify with, because the story is ultimately about people, and it’s about conflict and struggle.It’s important to realize that Chinatown and Japantown existed because of immigration restrictions. In 1972, I wrote this article called “Remembering 1882.” It was about the Chinese Exclusion Act, and there was a lot of research into the anti-Asian laws. There’s a lot of history and background to this site, which still survives as Japantown, and the roots of that were in the Anti-Asian Laws.There was a fence that was built when Chinatown was new (an eight-foot high fence that was covered with barbed wire originally surrounded Heinlenville). The fence was locked up every night by Charlie (community leaders hired Charlie, a white security guard who patrolled the area). Gradually, there was no fear of people who could come and burn another Chinatown down. The fence was to protect the Chinese, he said, so no one could get in, and no one could get out.Leslie: Basically, I was into the historic preservation of buildings, because they were tearing down all of downtown San Jose. And the building I was in, they tore up under it, so I got into history and got into general local history.The community doesn’t know its history. The individual histories aren’t there, much less the history of Japantown, Northside, and other neighborhoods. While we start developing things, everything gets wiped out. And people keep saying that San Jose has no soul and I say that’s because we keep erasing things. You don’t celebrate. You don’t build on something. You just keep wiping it out, and then it begins to look like everything else.The sad thing about San Jose is that just about all of the Chinese experience has disappeared. There are a lot of Chinese in the Valley, but there’s no particular Chinese place. There’s no town. There’s not even an event center.Now that these communities like Japantown are over 100 years old, it’s important to maintain what’s there. We want the community to prosper, but we also want to celebrate and commemorate the past and what’s there.That’s great that you have those anecdotes about the interaction between the Japanese and the Chinese communities.Connie: These were Asian American activities, but the cultures of China and Japan are so different, and a perfect example is the theater. Chinese theater is so elaborate and Japanese theater is very different. The Japanese had sumo wrestling, which the Chinese did not. There is an anecdote from a woman that I interviewed. She remembered that her mother said, “there’s a half naked man down the street!” It was a sumo wrestler doing an exhibition. They were very shocked because the Chinese never dressed like that.Leslie: This area was the center of the shopping, and the social life, and everything else. Even though all the Asians farmed, they would come here to do the shopping, to go to church, to do things, and some of it’s really interesting is to see where that interplay is. One of the things in the exhibit is a check that my grandfather wrote, but it’s made out to the Tek Wo board. Obviously they were trading with each other and they were buying from different stores, but they were very distinct communities. The interaction wasn’t necessarily at the personal level; it was not necessarily that people would go to the same churches, or the same social clubs, but there was this community interplay. Dr. Ishikawa (Dr. Tokio Ishikawa formerly owned the property where JAMsj currently resides) talks about buying lottery tickets from the Chinese that were around. And Grant Elementary School (near Japantown) was a mixed school. You can see the pictures.Why do you think that there is not a greater general awareness of early Chinatowns and Japantowns and how they have contributed to the present day?Leslie: The problem with history in schools, is that they try and cram in the big picture, the mainstream idea, and it tends to be East Coast dominated.Everybody hears about Ellis Island, but nobody hears really about Angel Island. Even teachers don’t know. They may know that these (Asian) people came in the 1850’s and that the Chinese worked on the railroads, but that’s it.The problem is, Connie’s book really is about the only book out there that’s about Chinatown in San Jose. So you don’t get the whole picture, you get one little story and then you have to go look for it. We just don’t have a mechanism where people are learning the history.Connie: I always go back to the Chinese Exclusion Act. When you exclude a people, there’s a disconnect. Their immigration is interrupted. And when it’s interrupted, it becomes a blank story.After the exclusion law was repealed, people had a hard time talking about the past. The exclusion law separated families and excluded Asians from American society. When you’re excluded, you don’t write about it. You have no record, you are invisible. You’re not a citizen – you’re just a non-entity.From 1882 to 1943, laborers were excluded and their history was obliterated. Most history is written from the point of the victors – the businesses, or the leaders. The laborers are omitted.And you know what happened - that’s why all the Chinatowns faded. It was a cultural center, and it was a home base for agricultural workers. So you have Chinese workers, and then Japanese, and then after when the Japanese were excluded and persecuted, you have the Mexicans, and then the Filipinos. There are people who specialize in labor history, and there are books on labor, but who would want to write about labor, except people who really were affected by it.

Connie Young Yu and Leslie Masunaga are JAMsj guest curators. They are currently working on the new JAMsj exhibit, "Common Ground: Chinatown and Japantown, San Jose," which will open in September of 2012. They sat down with interviewer, Nancy Yang, to discuss their vision for the exhibit.What inspired you to create this exhibit? Was there anything in your own life experience that drove you to create the exhibit? Connie: I grew up hearing about my parents and their oral history. My father was born on Cleveland Avenue (in Heinlenville, which no longer exists. Heinlenville was a Chinatown that would be located within the boundaries of present day San Jose Japantown). He was in his twenties when he left the 6th street settlement. My father was actually there until 1937. So his memories were very strong.He remembered Japantown and having Japanese neighbors. He saw the transformation from Chinatown to Japantown. This is what I think is really exciting. I feel that this site of Cleveland Avenue, of Sixth Street, and Jackson Street was the birthplace of the first Asian American community in Santa Clara Valley. It was no longer just Chinatown, and no longer just Japantown. More Asians moved in including Filipinos. This was really the first multicultural place.I think that the story (about Chinatown and Japantown) is very inspiring. You want to reach people in a way that they can understand and identify with, because the story is ultimately about people, and it’s about conflict and struggle.It’s important to realize that Chinatown and Japantown existed because of immigration restrictions. In 1972, I wrote this article called “Remembering 1882.” It was about the Chinese Exclusion Act, and there was a lot of research into the anti-Asian laws. There’s a lot of history and background to this site, which still survives as Japantown, and the roots of that were in the Anti-Asian Laws.There was a fence that was built when Chinatown was new (an eight-foot high fence that was covered with barbed wire originally surrounded Heinlenville). The fence was locked up every night by Charlie (community leaders hired Charlie, a white security guard who patrolled the area). Gradually, there was no fear of people who could come and burn another Chinatown down. The fence was to protect the Chinese, he said, so no one could get in, and no one could get out.Leslie: Basically, I was into the historic preservation of buildings, because they were tearing down all of downtown San Jose. And the building I was in, they tore up under it, so I got into history and got into general local history.The community doesn’t know its history. The individual histories aren’t there, much less the history of Japantown, Northside, and other neighborhoods. While we start developing things, everything gets wiped out. And people keep saying that San Jose has no soul and I say that’s because we keep erasing things. You don’t celebrate. You don’t build on something. You just keep wiping it out, and then it begins to look like everything else.The sad thing about San Jose is that just about all of the Chinese experience has disappeared. There are a lot of Chinese in the Valley, but there’s no particular Chinese place. There’s no town. There’s not even an event center.Now that these communities like Japantown are over 100 years old, it’s important to maintain what’s there. We want the community to prosper, but we also want to celebrate and commemorate the past and what’s there.That’s great that you have those anecdotes about the interaction between the Japanese and the Chinese communities.Connie: These were Asian American activities, but the cultures of China and Japan are so different, and a perfect example is the theater. Chinese theater is so elaborate and Japanese theater is very different. The Japanese had sumo wrestling, which the Chinese did not. There is an anecdote from a woman that I interviewed. She remembered that her mother said, “there’s a half naked man down the street!” It was a sumo wrestler doing an exhibition. They were very shocked because the Chinese never dressed like that.Leslie: This area was the center of the shopping, and the social life, and everything else. Even though all the Asians farmed, they would come here to do the shopping, to go to church, to do things, and some of it’s really interesting is to see where that interplay is. One of the things in the exhibit is a check that my grandfather wrote, but it’s made out to the Tek Wo board. Obviously they were trading with each other and they were buying from different stores, but they were very distinct communities. The interaction wasn’t necessarily at the personal level; it was not necessarily that people would go to the same churches, or the same social clubs, but there was this community interplay. Dr. Ishikawa (Dr. Tokio Ishikawa formerly owned the property where JAMsj currently resides) talks about buying lottery tickets from the Chinese that were around. And Grant Elementary School (near Japantown) was a mixed school. You can see the pictures.Why do you think that there is not a greater general awareness of early Chinatowns and Japantowns and how they have contributed to the present day?Leslie: The problem with history in schools, is that they try and cram in the big picture, the mainstream idea, and it tends to be East Coast dominated.Everybody hears about Ellis Island, but nobody hears really about Angel Island. Even teachers don’t know. They may know that these (Asian) people came in the 1850’s and that the Chinese worked on the railroads, but that’s it.The problem is, Connie’s book really is about the only book out there that’s about Chinatown in San Jose. So you don’t get the whole picture, you get one little story and then you have to go look for it. We just don’t have a mechanism where people are learning the history.Connie: I always go back to the Chinese Exclusion Act. When you exclude a people, there’s a disconnect. Their immigration is interrupted. And when it’s interrupted, it becomes a blank story.After the exclusion law was repealed, people had a hard time talking about the past. The exclusion law separated families and excluded Asians from American society. When you’re excluded, you don’t write about it. You have no record, you are invisible. You’re not a citizen – you’re just a non-entity.From 1882 to 1943, laborers were excluded and their history was obliterated. Most history is written from the point of the victors – the businesses, or the leaders. The laborers are omitted.And you know what happened - that’s why all the Chinatowns faded. It was a cultural center, and it was a home base for agricultural workers. So you have Chinese workers, and then Japanese, and then after when the Japanese were excluded and persecuted, you have the Mexicans, and then the Filipinos. There are people who specialize in labor history, and there are books on labor, but who would want to write about labor, except people who really were affected by it.

Heinlenville Exhibit Opens in September 2012

By Nancy Yang

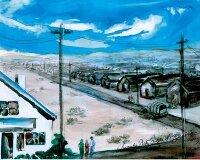

This September, guest curators Connie Young Yu and Leslie Masunaga will unveil a special exhibit, "Common Ground: Chinatown and Japantown, San Jose," at JAMsj that focuses on the story of Heinlenville, San Jose’s last Chinatown. Yu is the author of Chinatown, San Jose, USA, now in its fourth edition. The new JAMsj exhibit will focus on the personal story behind Heinlenville’s residents and chronicle that community’s relationship to and influence on current-day Japantown.The exhibit will feature artifacts from a 2008 Sonoma State University archaeological excavation of the Heinlenville site. Included in the collection are personal mementos of the curators, including a check made out by Masunaga’s grandfather to the Tuck Wo store, and objects from Yu’s family. There will also be a video associated with the exhibit that incorporates photos and interviews.The construction of San Jose’s last Chinatown began in 1887, several months after arson destroyed the Market Street Chinatown. Heinlenville was bordered by Fifth, Seventh, Jackson, and Taylor streets. It was established at a time of great anti-Asian sentiment, amid calls by city leaders and citizens for the complete elimination of Chinese settlements within the city’s perimeters. Heinlenville was originally surrounded by an eight-foot high fence covered with barbed wire to protect the Chinese from anti-Chinese elements.The namesake of the town is John Heinlen, a German American immigrant and businessman who defied convention in the 1880s by agreeing to lease land to the Chinese and Japanese in San Jose. His defiant actions, made during a time when strong nativist passions were also rampant, still resonate with us today.“I feel San Jose should feel very proud,” Yu said. “Having someone like John Heinlen made a huge difference. If it weren’t for him, I think that we (San Jose) would probably have a very bleak racial image. He’s the greatest example of somebody doing good for the community and rising above (the racial turmoil). I feel that if we do anything, it’s to keep the history, the memory, and the inspiration of John Heinlen alive.”A shared emphasis of their past projects was a focus on community education, through both open houses and public outreach. Yu recalls, “For two years in a row, Leslie and I did our own exhibit. We just put up picnic tables. We had the artifacts and memorabilia, and people could come by and take a look.”“There’s something tangible, in having something to touch and see,” says Masunaga about the artifacts. “It’s something that connects to you as opposed to seeing something in a book, or on paper, or something that just becomes very academic and very cold.” Tangible items, such as boar’s teeth, marbles, and jade bracelets, in conjunction with photographs and anecdotes, help to elucidate the daily life of Heinlenville. This combination also illuminates the quiet dignity of citizens, in the face of outside hostility.This personal approach to history is echoed in the Heinlenville exhibit, as the curators’ vision is to celebrate the colorful life and history of Chinatown and its relationship to present-day Japantown. “I think this is an opportunity to say that this place existed, in terms of a physical community,” says Masunaga. “We want to really bring that aspect forward and give more depth to the community that’s here today--not just to the Japanese American community, but also to the local scene--and to understand the interplay between the communities.”Masunaga notes the significance of telling the Chinese American story. “The sad thing about San Jose is that just about all of the Chinese experience has disappeared. There are a lot of Chinese in the Valley, but there’s no particular Chinese place. There’s no town. There’s not even an event center."Yu reflects on the deeper meaning of the exhibit, “It’s really an all-American story. They’d always say, ‘that’s your history,’ or they’d call it ethnic history. But I would say no. I’m talking about American history. And when Leslie talks about local history, she’s talking about our roots. It’s not strictly Asian American history, and it is not a story about ‘you guys.’”Both curators have deep roots in the Bay Area and have worked extensively together as a team. The two first met in 1990 when Masunaga was working as an archivist at the San Jose Historical Museum, and Yu was working on the book, Chinatown, San Jose, USA.

The Story of the 120,000 Tassel Tapestry

Leila Kubesh, the teacher who inspired her 8th grade students to create the 120,000 Tassel Tapestry, will be coming to JAMsj on June 23, 2012 to talk about her project.The Story of the 120,000 Tassel Tapestry By Leila Kubesch and Steve Fugita The amazing story of the 120,000 Tassel Tapestry began in Indiana, where foreign language teacher Leila Kubesch taught French, Spanish, and Japanese to 8th graders at Sunnyside and Tecumseh Middle Schools. As part of her responsibilities, Leila directed the foreign language club. Each year this club took on special interest projects. The project that holds a special interest to JAMsj was the creation of a grand quilt commemorating the Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in concentration camps during WWII.Initially, Leila started teaching the history of Americans of Japanese Ancestry (AJAs) to encourage students to stop mocking Asians. She began by reading books such as The Bracelet and Hero. A few students were puzzled and asked, “Is this true?” They had never heard anything about Japanese American history before.

The amazing story of the 120,000 Tassel Tapestry began in Indiana, where foreign language teacher Leila Kubesch taught French, Spanish, and Japanese to 8th graders at Sunnyside and Tecumseh Middle Schools. As part of her responsibilities, Leila directed the foreign language club. Each year this club took on special interest projects. The project that holds a special interest to JAMsj was the creation of a grand quilt commemorating the Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in concentration camps during WWII.Initially, Leila started teaching the history of Americans of Japanese Ancestry (AJAs) to encourage students to stop mocking Asians. She began by reading books such as The Bracelet and Hero. A few students were puzzled and asked, “Is this true?” They had never heard anything about Japanese American history before. The students decided to turn the school courtyard into a Japanese Zen garden to honor the 100th Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The next year, the second class added a large pond. In 2000, when the students learned about other military units like the 1800th, the MIS, and 522nd, they wanted them to be included, too. Their dream culminated in the building of a traveling exhibit that could be shown across America. The exhibit would involve the making of a very special quilt.During the first semester of the next academic year, the tapestry was started at Tecumseh Middle School. In the beginning, the students were often told, “It cannot be done.” Leila was even turned down for a grant on the grounds that the project was too ambitious. To initiate the project, the students obtained a comprehensive list of AJA veterans from military archives. Using this list, they mailed more than 3,000 letters to the veterans. Many of the recipients wrote back and even sent their historic mementos.When Leila moved to Sunnyside Middle School for the second semester, many students followed so that they could continue working on the project. During the summer, students from both schools worked together until it was complete. This included weekends and holidays. Often, students and teacher went home past midnight. This brought the two rival schools, one well-to-do, the other inner city, closer together. Many of the students became good friends. Ultimately, 503 students from Sunnyside and Tecumseh Middle Schools worked on the quilt. When it was finished, it was proudly hung for the first time in the school gymnasium.The students named the quilt the 120,000 Tassel Tapestry to represent all of the AJAs who endured WWII injustices. It measures 19 by 41 feet, dimensions chosen to represent 1941, the year in which Pearl Harbor was attacked. It comes in 12 panels and looks like a Japanese shop curtain called noren. Because someone told the students that the kanji for noren is similar to the word ”goodwill,” they insisted on using the noren style. The tapestry weighs some 350 pounds.In 2008, Leila married and moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where she teaches English as a Second Language at Sharonville Elementary School. But her Indiana students will never forget the special projects she inspired them to take on, in particular the 120,000 Tassel Tapestry. --------------------------------------------------------------Leila will talk about the 120,000 Tassel Tapestry at 1:00 p.m on June 23 at JAMsj. Please reserve your seat by contacting the JAMsj office (408) 294-3138 or by emailing events@jamsj.org.

The students decided to turn the school courtyard into a Japanese Zen garden to honor the 100th Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The next year, the second class added a large pond. In 2000, when the students learned about other military units like the 1800th, the MIS, and 522nd, they wanted them to be included, too. Their dream culminated in the building of a traveling exhibit that could be shown across America. The exhibit would involve the making of a very special quilt.During the first semester of the next academic year, the tapestry was started at Tecumseh Middle School. In the beginning, the students were often told, “It cannot be done.” Leila was even turned down for a grant on the grounds that the project was too ambitious. To initiate the project, the students obtained a comprehensive list of AJA veterans from military archives. Using this list, they mailed more than 3,000 letters to the veterans. Many of the recipients wrote back and even sent their historic mementos.When Leila moved to Sunnyside Middle School for the second semester, many students followed so that they could continue working on the project. During the summer, students from both schools worked together until it was complete. This included weekends and holidays. Often, students and teacher went home past midnight. This brought the two rival schools, one well-to-do, the other inner city, closer together. Many of the students became good friends. Ultimately, 503 students from Sunnyside and Tecumseh Middle Schools worked on the quilt. When it was finished, it was proudly hung for the first time in the school gymnasium.The students named the quilt the 120,000 Tassel Tapestry to represent all of the AJAs who endured WWII injustices. It measures 19 by 41 feet, dimensions chosen to represent 1941, the year in which Pearl Harbor was attacked. It comes in 12 panels and looks like a Japanese shop curtain called noren. Because someone told the students that the kanji for noren is similar to the word ”goodwill,” they insisted on using the noren style. The tapestry weighs some 350 pounds.In 2008, Leila married and moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where she teaches English as a Second Language at Sharonville Elementary School. But her Indiana students will never forget the special projects she inspired them to take on, in particular the 120,000 Tassel Tapestry. --------------------------------------------------------------Leila will talk about the 120,000 Tassel Tapestry at 1:00 p.m on June 23 at JAMsj. Please reserve your seat by contacting the JAMsj office (408) 294-3138 or by emailing events@jamsj.org.

Juri Kameda Conquers All Odds and Lives Life to the Fullest

On Saturday, April 14, Juri Kameda jumped out of a plane to raise awareness and money and for the ALS Therapy Development Institute. Juri is a friend of JAMsj and her beautiful jewelry is sold in the museum's store. JAMsj President Aggie Idemoto interviewed Juri before her jump.

Juri Kameda Conquers All Odds and Lives Life to the Fullest

By Aggie Idemoto

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6jzYYeOMzIs]

Japan-born Juri Kameda immigrated to the U.S. and her life has since been one of transitions. Her most recent career change as a jeweler connected her to JAMsj.

Juri attended Japanese and Catholic schools in Japan until the fifth grade, when she transitioned to an American education. This change meant a shift in educational methodology and expectations, as well as languages. Juri is fluent in Japanese, English, Spanish and has a conversational grasp of Mandarin. With her diverse language skills, she aspired to work with the United Nations, but her parents steered her toward a career in medicine or technology. “There’s no money working for a non-profit,” they cautioned.After studying at Foothill Community College and U.C. San Diego with a major in cognitive science, Juri began her career as a certified respiratory care practitioner. She then moved into the technology world as a simultaneous translator. When her 2-year-old son started violin lessons and needed larger violins as he grew up, Juri began to make his violins herself. These experiences lead to her position with the Kamimoto String Instruments shop in Japantown, making and repairing violins and cellos.In her spare time, Juri plays the flute, and for the past ten years has been an avid abalone diver. She and her husband, Ken, are world travelers, making one major trip every two years.In 2005, she experienced the biggest transition of her life when she was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. This neurological disease causes muscle weakness, disability, and eventually death. There is no known cure. The news struck a devastating blow, but did not crimp any plans for Juri.During a trip to Helsinki three years ago, she discovered and was enthralled by a unique form of glass jewelry, which instantly inspired her to go into the making of glass jewelry. Her disability requires the assistance of a wheel chair, respirator, and service dog, but Juri has use of three fingers in both hands and puts her creative outlet, energy, and vitality for living into each of her hand-crafted creations. A jeweler for over a year, her creations are featured in the JAMsj store. She contributes 5% of her proceeds to ALS Guardian Angels.When asked what message she wants to shout out to others, she did not hesitate with the following: “Live life like there’s no tomorrow. Live for the moment and don’t dwell on the unknown.” Juri Kameda is a truly inspiring role model for all of us.On Saturday, Juri Kameda and her friend, Gloria Hale, a San Jose resident who is also diagnosed with ALS, made the jump to raise awareness for the disease. To make a donation in support of Juri Kameda , Gloria Hale, and the ALS Therapy Development Institute, go to http://community.als.net/skydiveforYFALS.

A jeweler for over a year, her creations are featured in the JAMsj store. She contributes 5% of her proceeds to ALS Guardian Angels.When asked what message she wants to shout out to others, she did not hesitate with the following: “Live life like there’s no tomorrow. Live for the moment and don’t dwell on the unknown.” Juri Kameda is a truly inspiring role model for all of us.On Saturday, Juri Kameda and her friend, Gloria Hale, a San Jose resident who is also diagnosed with ALS, made the jump to raise awareness for the disease. To make a donation in support of Juri Kameda , Gloria Hale, and the ALS Therapy Development Institute, go to http://community.als.net/skydiveforYFALS.

Bridging Communities the Oy Way

L ong-time JAMsj supporter Harvey Gotliffe organized several Gathering of Friends events that brought together former Japanese American internees and Holocaust survivors so that they could discuss their own personal stories. At the first Gathering of Friends event in 2005, a Holocaust survivor was sitting next to a former Japanese American internee, and held up a sign and said, “This is my name in Japanese.” Her new found friend held up a sign that the survivor had made, and proudly proclaimed, “This is my name in Yiddish.”

ong-time JAMsj supporter Harvey Gotliffe organized several Gathering of Friends events that brought together former Japanese American internees and Holocaust survivors so that they could discuss their own personal stories. At the first Gathering of Friends event in 2005, a Holocaust survivor was sitting next to a former Japanese American internee, and held up a sign and said, “This is my name in Japanese.” Her new found friend held up a sign that the survivor had made, and proudly proclaimed, “This is my name in Yiddish.” While few members of the Japanese American community were able to speak Yiddish, Harvey has published a book that might help resolve that situation. The Oy Way is an entertaining book that helps readers learn thirty-six Yiddish expressions while engaging in a restorative, meditative, moving exercise experience.If you want to learn about The Oy Way, just click here to get to the author's web site, and be prepared to speak a bisl (bit of) Yiddish by the next Gathering of Friends.

While few members of the Japanese American community were able to speak Yiddish, Harvey has published a book that might help resolve that situation. The Oy Way is an entertaining book that helps readers learn thirty-six Yiddish expressions while engaging in a restorative, meditative, moving exercise experience.If you want to learn about The Oy Way, just click here to get to the author's web site, and be prepared to speak a bisl (bit of) Yiddish by the next Gathering of Friends.

Anniversary of infamy for American freedoms

Local journalist and writer Marty Cheek has been a friend of JAMsj for many years. Marty wrote the following article on the 70th anniversary of Executive Order 9066. This article was originally published in the Gilroy Dispatch on February 24, 2012.By Marty CheekLast Sunday marked an anniversary of infamy for American freedom.That sunny day in the South Valley marked 70 years since President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave the U.S. military broad powers to force 120,000 American citizens to leave their homes and possessions to be relocated behind the barbed-wire fences of concentration camps in desolate locations. I consider Roosevelt's decision on Feb. 19, 1942 to sign Executive Order 9066 one of the most atrocious failings by a U.S. president in upholding America's traditions of freedom and democracy. Many argued then - as some argue now - that the president was required to place American citizens of Japanese ancestry in internment camps during World War II as a national defense measure. Roosevelt defended his decision by saying the "successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage." Refuting that argument is the fact that there was never one proven case of a Japanese-American citizen during the war participating in an action of sabotage, espionage or otherwise assisting the enemy. Considering the evidence that has emerged in recent decades, the true reason for the "evacuation" of Japanese-American citizens was racism and a desire by some to suppress economic competition.Not long after the evacuation started, and many of these citizens, including families in the South Valley region, were rounded up and taken to assembly centers. A music teacher in California's San Joaquin Valley wrote these words as part of a three-page statement he presented to U.S. Army officers at a hearing at the Presidio military base in San Francisco:"True democracy, while recognizing the right of the majority to rule, is also unique in the position established by the fathers of this country in recognizing the rights of the minority. That is the reason why the really democratic form of government is superior to all others. Democracy recognizes the right of the individual to freedom of conscience and religious worship. That right must be carefully guarded by all Christians and believers in true democracy. The spirit of democracy in this respect must not be destroyed in times of national stress or emergency. It is far too valuable to be lost by the efforts of those who have forgotten the real value of life."I happened to come across the document containing those words while going through a box of old papers. The irony struck me that I found the testimony the day before the 70th anniversary of President Roosevelt's signing of Executive Order 9066. The document had a double impact on me because I am reading the book "The Muslim Next Door: The Qur'an, the Media, and that Veil Thing" by Sumbul Ali-Karamali. As an event for the Silicon Valley Reads program, I'll conduct a public discussion of the book at the Morgan Hill Library on March 10.Sept. 11 is my generation's Pearl Harbor. The surprise attack by terrorists 10 years ago and its aftermath has parallels with the Japanese military's strike on the U.S. Navy base in Honolulu and the hysteria that spawned injustice for Japanese Americans. As part of the aftermath of Sept. 11, our nation is dealing with religious prejudice toward Muslim Americans. This prejudice has prompted some politicians to stir up the hysteria of 9/11 and promote legally sanctioned discrimination, in the form of anti-Sharia laws, against those who follow the faith of Islam.Political representatives in more than a dozen states have worked on legislation to outlaw traditional Islamic laws in the United States. Congresswoman Michele Bachmann has advocated the suppression of Islamic religious law, stating that the intention of Muslims is to "usurp" the U.S. Constitution with Sharia. And Republican presidential candidate Newt Gingrich has told supporters "Sharia is a mortal threat to the survival of freedom in the United States and in the world and we know it."Let me tell you about that teacher who wrote the statement for the U.S. Army hearing. He was a proud Republican because he believed that his political party exemplified the legacy of Lincoln, a legacy of liberty. That man was my father, Raymond Cheek. By the end of 1942, my dad would go to the Tule Lake Internment Camp in a high desert valley near the California-Oregon border to teach music to young Japanese-American children behind barbed-wire fences because they were considered enemies of the United States.America is an exceptional nation. In our past, we have risen above our racial and religious bigotries. To uphold our traditions of freedom and democracy, we must remember to do so again.-------------------------------------------------------------------------------Marty Cheek is a journalist who resides in the city of Morgan Hill. His father Raymond Cheek taught music at the Tule Lake Internment Camp. He can be reached at martin.cheek@gmail.com

Many argued then - as some argue now - that the president was required to place American citizens of Japanese ancestry in internment camps during World War II as a national defense measure. Roosevelt defended his decision by saying the "successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage." Refuting that argument is the fact that there was never one proven case of a Japanese-American citizen during the war participating in an action of sabotage, espionage or otherwise assisting the enemy. Considering the evidence that has emerged in recent decades, the true reason for the "evacuation" of Japanese-American citizens was racism and a desire by some to suppress economic competition.Not long after the evacuation started, and many of these citizens, including families in the South Valley region, were rounded up and taken to assembly centers. A music teacher in California's San Joaquin Valley wrote these words as part of a three-page statement he presented to U.S. Army officers at a hearing at the Presidio military base in San Francisco:"True democracy, while recognizing the right of the majority to rule, is also unique in the position established by the fathers of this country in recognizing the rights of the minority. That is the reason why the really democratic form of government is superior to all others. Democracy recognizes the right of the individual to freedom of conscience and religious worship. That right must be carefully guarded by all Christians and believers in true democracy. The spirit of democracy in this respect must not be destroyed in times of national stress or emergency. It is far too valuable to be lost by the efforts of those who have forgotten the real value of life."I happened to come across the document containing those words while going through a box of old papers. The irony struck me that I found the testimony the day before the 70th anniversary of President Roosevelt's signing of Executive Order 9066. The document had a double impact on me because I am reading the book "The Muslim Next Door: The Qur'an, the Media, and that Veil Thing" by Sumbul Ali-Karamali. As an event for the Silicon Valley Reads program, I'll conduct a public discussion of the book at the Morgan Hill Library on March 10.Sept. 11 is my generation's Pearl Harbor. The surprise attack by terrorists 10 years ago and its aftermath has parallels with the Japanese military's strike on the U.S. Navy base in Honolulu and the hysteria that spawned injustice for Japanese Americans. As part of the aftermath of Sept. 11, our nation is dealing with religious prejudice toward Muslim Americans. This prejudice has prompted some politicians to stir up the hysteria of 9/11 and promote legally sanctioned discrimination, in the form of anti-Sharia laws, against those who follow the faith of Islam.Political representatives in more than a dozen states have worked on legislation to outlaw traditional Islamic laws in the United States. Congresswoman Michele Bachmann has advocated the suppression of Islamic religious law, stating that the intention of Muslims is to "usurp" the U.S. Constitution with Sharia. And Republican presidential candidate Newt Gingrich has told supporters "Sharia is a mortal threat to the survival of freedom in the United States and in the world and we know it."Let me tell you about that teacher who wrote the statement for the U.S. Army hearing. He was a proud Republican because he believed that his political party exemplified the legacy of Lincoln, a legacy of liberty. That man was my father, Raymond Cheek. By the end of 1942, my dad would go to the Tule Lake Internment Camp in a high desert valley near the California-Oregon border to teach music to young Japanese-American children behind barbed-wire fences because they were considered enemies of the United States.America is an exceptional nation. In our past, we have risen above our racial and religious bigotries. To uphold our traditions of freedom and democracy, we must remember to do so again.-------------------------------------------------------------------------------Marty Cheek is a journalist who resides in the city of Morgan Hill. His father Raymond Cheek taught music at the Tule Lake Internment Camp. He can be reached at martin.cheek@gmail.com

San Jose Congressional Gold Medal Ceremony

The U.S. Congress awarded the Congressional Gold Medal (CGM) to the U.S. Army’s 100th Infantry Battalion, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) and the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) for their extraordinary accomplishments in World War II.On February 23, 2012, the Japanese American Museum of San Jose (JAMsj), the San Jose Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), the Friends and Families of Nisei Veterans (FFNV), local VFW Post 9970, and the San Jose Buddhist Church Betsuin, in conjunction with Representatives Zoe Lofgren, Mike Honda, and Anna Eshoo, held a local ceremony honoring the veterans and their families in San Jose, California.A Congressional Gold Medal is an award bestowed by the United States Congress and is, along with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States. The decoration is awarded to an individual who performs an outstanding deed or act of service to the security, prosperity, and national interest of the United States.Clear here to view images from the San Jose Congressional Gold Medal event.

The U.S. Congress awarded the Congressional Gold Medal (CGM) to the U.S. Army’s 100th Infantry Battalion, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) and the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) for their extraordinary accomplishments in World War II.On February 23, 2012, the Japanese American Museum of San Jose (JAMsj), the San Jose Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), the Friends and Families of Nisei Veterans (FFNV), local VFW Post 9970, and the San Jose Buddhist Church Betsuin, in conjunction with Representatives Zoe Lofgren, Mike Honda, and Anna Eshoo, held a local ceremony honoring the veterans and their families in San Jose, California.A Congressional Gold Medal is an award bestowed by the United States Congress and is, along with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States. The decoration is awarded to an individual who performs an outstanding deed or act of service to the security, prosperity, and national interest of the United States.Clear here to view images from the San Jose Congressional Gold Medal event.

Echoes of Executive Order 9066

By Will KakuOn February 19, 2012, members of the San Jose community will commemorate the 70th anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066 at the 32nd Annual San Jose Day of Remembrance event. The executive order eventually led to the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The San Jose Day of Remembrance program, entitled “Civil Liberties Under Siege,” brings different communities together to remember the signing of the executive order -- which many people now acknowledge to be a great civil liberties tragedy – and attendees are encouraged to reflect on what that historical event means to their lives today.

Many people, especially within the Japanese American community, feel that important lessons can be extracted from the incarceration of Japanese Americans and that those lessons are pertinent to the issues of today.

Last week, President Obama signed the 2012 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which has a provision that allows for the indefinite detention of U.S. citizens without trial. Civil liberties groups, human rights advocates, and members of the Japanese American community have vehemently protested the signing of this bill. Congressman Mike Honda (D-CA), a former internee from Camp Amache and a frequent speaker at the San Jose Day of Remembrance event, voted against the NDAA and said that the bill did not have sufficient changes “to ensure the Constitutional rights of every U.S. citizen. For these reasons, I voted against the FY12 National Defense Authorization Act.”

Susan Hayase, a Nihonmachi Outreach Committee (NOC) chairperson during the redress movement and vice chairperson of the Civil Liberties Public Education Fund, commented about the dangers of the provision and drew parallels with internment. “Due process is something that my family holds precious,” Hayase said. “My entire family was detained indefinitely without charges, without a chance to defend themselves in court after being declared ‘enemy non-aliens’ by the U.S. government. We suffered deeply for this, but our American Constitution suffered even more.” Floyd Mori, national executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), wrote about his concerns over the Senate bill in an op-ed for the San Jose Mercury News. Mori claimed that the bill “raises the question of whether the Senate has forgotten our history.” Mori wrote, “Although the details of the indefinite detentions of Japanese Americans during World War II and the proposed indefinite detentions of terrorism suspects may differ, the principle remains the same: indefinite detentions based on fear-driven and unlawfully substantiated national security grounds, where individuals are neither duly charged nor fairly tried, violate the essence of U.S. law and the most fundamental values upon which this country was built."In the legal arena, the significance of Japanese internment has risen in a post-9/11 world. In an article for the Kansas Law Review (“Raising the Red Flag: The Continued Relevance of the Japanese Internment in the Post-Hamdi World”), University of Colorado Law School professor Aya Gruber, a daughter of a former internee, wrote that the “reminders of the horrors of internment remain highly relevant, as the United States continues to engage regularly in armed conflict and detain thousands of people without regard to constitutional safeguards or criminal process.” She concludes that, “Defenders of civil liberties must therefore continue to raise the red flag, be vigilant about government overreaching, and passionately invoke the caution of the internment.”

Floyd Mori, national executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), wrote about his concerns over the Senate bill in an op-ed for the San Jose Mercury News. Mori claimed that the bill “raises the question of whether the Senate has forgotten our history.” Mori wrote, “Although the details of the indefinite detentions of Japanese Americans during World War II and the proposed indefinite detentions of terrorism suspects may differ, the principle remains the same: indefinite detentions based on fear-driven and unlawfully substantiated national security grounds, where individuals are neither duly charged nor fairly tried, violate the essence of U.S. law and the most fundamental values upon which this country was built."In the legal arena, the significance of Japanese internment has risen in a post-9/11 world. In an article for the Kansas Law Review (“Raising the Red Flag: The Continued Relevance of the Japanese Internment in the Post-Hamdi World”), University of Colorado Law School professor Aya Gruber, a daughter of a former internee, wrote that the “reminders of the horrors of internment remain highly relevant, as the United States continues to engage regularly in armed conflict and detain thousands of people without regard to constitutional safeguards or criminal process.” She concludes that, “Defenders of civil liberties must therefore continue to raise the red flag, be vigilant about government overreaching, and passionately invoke the caution of the internment.” In the post-9/11 world, the Japanese American community has also been one of the most ardent supporters of embattled Muslim Americans. Last March, House Homeland Security Committee Chairman Peter T. King (R-N.Y.) launched controversial hearings on radical Islam in the United States. Congressman Honda stated in an op-ed for the San Francisco Chronicle, “Hundreds of thousands of innocent Japanese Americans were unjustly placed under scrutiny and suspicion because few in Washington were brave enough to say ‘no’.” Honda claimed that, “Representative King’s intent seems clear: To cast suspicion upon all Muslim Americans and to stoke the fires of anti-Muslim prejudice and Islamophobia.”

In the post-9/11 world, the Japanese American community has also been one of the most ardent supporters of embattled Muslim Americans. Last March, House Homeland Security Committee Chairman Peter T. King (R-N.Y.) launched controversial hearings on radical Islam in the United States. Congressman Honda stated in an op-ed for the San Francisco Chronicle, “Hundreds of thousands of innocent Japanese Americans were unjustly placed under scrutiny and suspicion because few in Washington were brave enough to say ‘no’.” Honda claimed that, “Representative King’s intent seems clear: To cast suspicion upon all Muslim Americans and to stoke the fires of anti-Muslim prejudice and Islamophobia.” Several months before the congressional hearings, the plans to build an Islamic center near the site of the World Trade Center – which some people called the “mosque near ground-zero” -- stirred many powerful emotions on both sides of the heated debate. Within the Japanese American community, there were many visible signs of support for the center and for the Muslim American community. The JACL compared the current debate to the fiery controversy surrounding the establishment of a New York City hostel that housed Japanese Americans who were trying to resettle after leaving internment camps. The JACL stated that, “In the face of war and the tragedy of September 11, it is too easy to place blame on others and allow intolerance to prevail. We must do better than to leave Muslim Americans with the impression that intolerance has no definite end. We must begin by not reinterpreting our emotions over September 11 but instead by affirming the ideals that have defined our democracy.”There are also echoes of internment in other areas that concern civil rights and discrimination. Some people have called the fight for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) equality the next great civil rights battle of this decade. Many legal observers have claimed that California’s battle over Proposition 8 will soon be headed to the United States Supreme Court. Japanese American individuals and organizations, such as the National JACL, Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress (NCRR), and San Jose’s NOC, have strongly endorsed marriage equality and have made direct comparisons to past discriminatory laws directed toward Japanese Americans. Actor and activist, George Takei, drew personal comparisons with this act of discrimination to his own incarceration in an internment camp in a 2006 interview with Scott Simon on National Public Radio. Takei said, “I went to school in a black tar-paper barrack (as a child in internment camps) and began the day seeing the barbed-wire fence. Thank God those barbed-wire fences are now long gone for Japanese Americans. But I still see an invisible, legalistic barbed-wire that keeps me, my partner of 19 years, Brad Altman, and another group of Americans separated from a normal life.”Over the last several years, references to Japanese American internment and discrimination have recently made their way into many diverse issues such as airport racial profiling, the USA Patriot Act, the Habeas Corpus Restoration Act, the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System, the Federal Intelligence Security Act, presidential wartime powers, and even the Texas Board of Education textbook controversy. It is not surprising since the trauma of internment has indelibly shaped the values, attitudes, and political beliefs of many within the Japanese American community.-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Each year, the Nihonmachi Outreach Committee (NOC) hosts the San Jose Day of Remembrance event. The San Jose Day of Remembrance event will be held from 5:30 p.m to 7:30 p.m, on February 19, 2012, at the San Jose Buddhist Church Betsuin, located at 640 N. Fifth Street, San Jose, California. For more information, visit www.sjnoc.org.

Several months before the congressional hearings, the plans to build an Islamic center near the site of the World Trade Center – which some people called the “mosque near ground-zero” -- stirred many powerful emotions on both sides of the heated debate. Within the Japanese American community, there were many visible signs of support for the center and for the Muslim American community. The JACL compared the current debate to the fiery controversy surrounding the establishment of a New York City hostel that housed Japanese Americans who were trying to resettle after leaving internment camps. The JACL stated that, “In the face of war and the tragedy of September 11, it is too easy to place blame on others and allow intolerance to prevail. We must do better than to leave Muslim Americans with the impression that intolerance has no definite end. We must begin by not reinterpreting our emotions over September 11 but instead by affirming the ideals that have defined our democracy.”There are also echoes of internment in other areas that concern civil rights and discrimination. Some people have called the fight for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) equality the next great civil rights battle of this decade. Many legal observers have claimed that California’s battle over Proposition 8 will soon be headed to the United States Supreme Court. Japanese American individuals and organizations, such as the National JACL, Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress (NCRR), and San Jose’s NOC, have strongly endorsed marriage equality and have made direct comparisons to past discriminatory laws directed toward Japanese Americans. Actor and activist, George Takei, drew personal comparisons with this act of discrimination to his own incarceration in an internment camp in a 2006 interview with Scott Simon on National Public Radio. Takei said, “I went to school in a black tar-paper barrack (as a child in internment camps) and began the day seeing the barbed-wire fence. Thank God those barbed-wire fences are now long gone for Japanese Americans. But I still see an invisible, legalistic barbed-wire that keeps me, my partner of 19 years, Brad Altman, and another group of Americans separated from a normal life.”Over the last several years, references to Japanese American internment and discrimination have recently made their way into many diverse issues such as airport racial profiling, the USA Patriot Act, the Habeas Corpus Restoration Act, the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System, the Federal Intelligence Security Act, presidential wartime powers, and even the Texas Board of Education textbook controversy. It is not surprising since the trauma of internment has indelibly shaped the values, attitudes, and political beliefs of many within the Japanese American community.-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Each year, the Nihonmachi Outreach Committee (NOC) hosts the San Jose Day of Remembrance event. The San Jose Day of Remembrance event will be held from 5:30 p.m to 7:30 p.m, on February 19, 2012, at the San Jose Buddhist Church Betsuin, located at 640 N. Fifth Street, San Jose, California. For more information, visit www.sjnoc.org.

The Emotional Journey into Camp Days

The following article was written by JAMsj docent, Will Kaku. He reflects on the Chizuko Judy Sugita de Queiroz’ Camp Days 1942-1945 exhibit. The exhibit will be closing on December 30, 2011.

The Emotional Journey into Camp Days

By Will Kaku

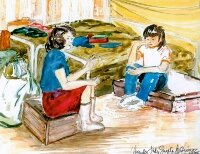

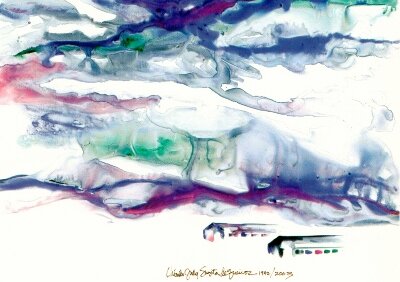

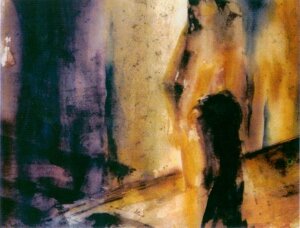

When the JAMsj reopened in October 2010, I used to start my tours like many docents do: in chronological order starting with the story of Chinese and Japanese immigration, the insatiable appetite for cheap labor by agribusiness and industrialists, the impact of racial attitudes and anti-Asian exclusionary laws, and the transition of an immigrant population from a “bachelor society” to one of permanence in San Jose’s Japantown. To me, to start from the beginning was the only way to tell this story.That is how many of us learned history in school. We were often immersed in historical timelines, the identification of key events, influential innovations, political leaders and movements, and the study of causality. There were many facts that had to be understood, necessitating a firm grasp on the “who, what, why, when, and where” of history.When it came to Chizuko Judy Sugita de Quieroz’ watercolor art exhibit, Camp Days 1942-1945, it just didn’t seem to fit my linearly constructed, fact-driven narrative. I often concluded my tours informing my tour group that we also had an art exhibit room which they could walk through and enjoy at their own leisure.I just didn’t get it. I simply saw that there were brightly colored images on the exhibit walls that depicted slices of camp life. There didn’t seem to be any sense of connectivity and profundity, and it missed the opportunity to make an overt political statement. There were also several paintings done in a child-like manner. I could probably paint better than that, I thought.During my breaks, I used to sit and relax in the Camp Days exhibit room, enjoying quiet, introspective times. Letting my mind wander into Chizuko’s paintings, I would reflect on the many former internees that I had met. And eventually, I started to understand.Sometimes the appreciation of art is like that. Like a fine wine, you often can’t appreciate it until you are fully aware of its subtle complexity. You cannot viscerally connect to the work until you are able to unlock the deeply embedded emotional layers. Chizuko’s exhibit describes a young girl’s journey into womanhood and reveals a deeply personal, emotionally scarring reaction to internment, a reaction that many former internees can identify with. For many in the Japanese American community, the repercussions of internment define who we are, shaping our values, political beliefs, and emotional character.In Chizuko’s work, there are basically two major styles represented in the exhibit: a representational form and an abstract form that embeds impressionistic components. Many of the representational forms are painted in a child-like manner, although it would be more accurate to say that they are painted through the eyes of a young Chizuko and layered with the knowledge of what was yet to come from the adult Chizuko.Chizuko had the most difficult time trying to create the abstract forms. Many of these paintings are heavily textured with deep emotions that include sorrow, loneliness, loss, and longing.

When the JAMsj reopened in October 2010, I used to start my tours like many docents do: in chronological order starting with the story of Chinese and Japanese immigration, the insatiable appetite for cheap labor by agribusiness and industrialists, the impact of racial attitudes and anti-Asian exclusionary laws, and the transition of an immigrant population from a “bachelor society” to one of permanence in San Jose’s Japantown. To me, to start from the beginning was the only way to tell this story.That is how many of us learned history in school. We were often immersed in historical timelines, the identification of key events, influential innovations, political leaders and movements, and the study of causality. There were many facts that had to be understood, necessitating a firm grasp on the “who, what, why, when, and where” of history.When it came to Chizuko Judy Sugita de Quieroz’ watercolor art exhibit, Camp Days 1942-1945, it just didn’t seem to fit my linearly constructed, fact-driven narrative. I often concluded my tours informing my tour group that we also had an art exhibit room which they could walk through and enjoy at their own leisure.I just didn’t get it. I simply saw that there were brightly colored images on the exhibit walls that depicted slices of camp life. There didn’t seem to be any sense of connectivity and profundity, and it missed the opportunity to make an overt political statement. There were also several paintings done in a child-like manner. I could probably paint better than that, I thought.During my breaks, I used to sit and relax in the Camp Days exhibit room, enjoying quiet, introspective times. Letting my mind wander into Chizuko’s paintings, I would reflect on the many former internees that I had met. And eventually, I started to understand.Sometimes the appreciation of art is like that. Like a fine wine, you often can’t appreciate it until you are fully aware of its subtle complexity. You cannot viscerally connect to the work until you are able to unlock the deeply embedded emotional layers. Chizuko’s exhibit describes a young girl’s journey into womanhood and reveals a deeply personal, emotionally scarring reaction to internment, a reaction that many former internees can identify with. For many in the Japanese American community, the repercussions of internment define who we are, shaping our values, political beliefs, and emotional character.In Chizuko’s work, there are basically two major styles represented in the exhibit: a representational form and an abstract form that embeds impressionistic components. Many of the representational forms are painted in a child-like manner, although it would be more accurate to say that they are painted through the eyes of a young Chizuko and layered with the knowledge of what was yet to come from the adult Chizuko.Chizuko had the most difficult time trying to create the abstract forms. Many of these paintings are heavily textured with deep emotions that include sorrow, loneliness, loss, and longing.

Uncertain Future depicts Chizuko’s family looking far off into the distance, contemplating what their future holds for them when they are finally released from the camp. Many people had great difficulty trying to recover their lives, and some encountered hostile reactions from their former communities. I once met Miyo Uzaki, a former internee, who told me that when she returned to her church in the Fresno area after the war, the pastor of her church informed her that he and the congregation did not want her family to return to the church. JAMsj curator, Jimi Yamaichi, remembered, “When we tried to move into our new home, the neighbors took a vote. We barely got in on a vote of 7 to 6.” Unanswered Prayers covers several major themes that flow throughout Camp Days. In camp, young Chizuko is told that, “If you pray hard enough, your prayers will come true.” Chizuko remarks, “Camp made me realize that my prayers would never be answered. I knew my mother would never come back to life, and I would never be a blue-eyed blond.” This idealized longing for a mother she never knew —she passed away when Chizuko was a baby – is captured in other images in the exhibit. Chizuko states, “Being motherless in camp had a detrimental impact on my childhood. I didn't have anyone. If I had a mother, I'm sure that she would have protected me and taken me every place with her. I wouldn't have had any traumatic experiences”“That painting is an abstract of me,” Chizuko told me. “I’m coming out of the cement shower room, so uncomfortable, sad, and depressed.” The naked body of Chizuko suggests great vulnerability, loneliness, and insecurity. Without her mother, the young Chizuko was becoming increasingly insecure about her body as she moved toward puberty. The lack of privacy in camp also made her feel extremely uncomfortable. Chizuko explained, “I was always embarrassed to shower with a lot of naked women.” In one painting, It’s Not Polite to Stare, she was told that she couldn’t play with her classmates because she had no mother and that she was rude because she stared at another woman in the shower.Her prayer to be non-Japanese in appearance obviously means that she would not have to be in camp if she were a “blue-eyed blond.” But, the wish also carries a deeper implication in the rejection of one’s self. Many of us who grew up in an exclusively Caucasian environment -- in a time when no Asian faces were represented on TV, in films , toys, commercials or magazines -- have harbored similar feelings of “wanting to be white” or a disdain and rejection of everything that was Japanese within ourselves.Other paintings in the exhibit convey similar themes. A Good American, Black and White Houses, Discovery and Disillusionment, and No Japs Allowed, reinforce her feeling of being a “bad person” and reveal her painful reaction to ostracism and discrimination.

Unanswered Prayers covers several major themes that flow throughout Camp Days. In camp, young Chizuko is told that, “If you pray hard enough, your prayers will come true.” Chizuko remarks, “Camp made me realize that my prayers would never be answered. I knew my mother would never come back to life, and I would never be a blue-eyed blond.” This idealized longing for a mother she never knew —she passed away when Chizuko was a baby – is captured in other images in the exhibit. Chizuko states, “Being motherless in camp had a detrimental impact on my childhood. I didn't have anyone. If I had a mother, I'm sure that she would have protected me and taken me every place with her. I wouldn't have had any traumatic experiences”“That painting is an abstract of me,” Chizuko told me. “I’m coming out of the cement shower room, so uncomfortable, sad, and depressed.” The naked body of Chizuko suggests great vulnerability, loneliness, and insecurity. Without her mother, the young Chizuko was becoming increasingly insecure about her body as she moved toward puberty. The lack of privacy in camp also made her feel extremely uncomfortable. Chizuko explained, “I was always embarrassed to shower with a lot of naked women.” In one painting, It’s Not Polite to Stare, she was told that she couldn’t play with her classmates because she had no mother and that she was rude because she stared at another woman in the shower.Her prayer to be non-Japanese in appearance obviously means that she would not have to be in camp if she were a “blue-eyed blond.” But, the wish also carries a deeper implication in the rejection of one’s self. Many of us who grew up in an exclusively Caucasian environment -- in a time when no Asian faces were represented on TV, in films , toys, commercials or magazines -- have harbored similar feelings of “wanting to be white” or a disdain and rejection of everything that was Japanese within ourselves.Other paintings in the exhibit convey similar themes. A Good American, Black and White Houses, Discovery and Disillusionment, and No Japs Allowed, reinforce her feeling of being a “bad person” and reveal her painful reaction to ostracism and discrimination.

When Chizuko speaks about Camp Days, it often leads to tears. Many of her emotions have been bottled up and suppressed over the years. Chizuko suffered great loneliness in camp. Her older siblings told her to just deal with her situation, saying “You’re not a baby anymore.” Much later in life, when she would bring up the topic of camp or her mother, “My brothers and sisters would just say that I just cried and whined all the time and that would end the conversation,” Chizuko explained.Chizuko now says that producing this exhibit was a cathartic experience for her. She normally paints outdoors, but when she painted Camp Days, she isolated herself in a room, revisiting many of the painful memories. All of the emotions that had been previously submerged and invalidated by others could no longer be held back. “I did a lot of gnashing of teeth, crying, laughing, while just remembering more and more details,” Chizuko recalled.The personal, emotional reaction to historical events is one that many people can identify with. During the hearings on redress in the 1980s, many people remember the sudden outpouring of long-held emotions. The emotional repercussions of internment define who many of us are as individuals and as a community. Armed with this deeper knowledge of Camp Days, the life of Chizuko Judy Sugita de Queiroz, and stories from many of the former internees that I have met, I now start rather than end my tours in the Camp Days exhibit. I am very thankful to have taken this emotional journey with Chizuko into Camp Days. This journey will remain with me for a long time.

To get more information from the artist, visit www.artbychiz.com.------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Yesterday's Farmer: Eiichi Edward Sakauye (1912-2005)

By Joe Yasutake I first got to know Eiichi when I spent several days with him while preparing for an extensive interview with him that was to be a part of a video history project. Our friendship blossomed when, at age 90, he decided that his night vision was not good enough to drive after dark. This decision resulted in my routinely picking him up to attend JAMsj board meetings and other evening events. During this period, I had the privilege of listening to many stories about his fascinating life--from his childhood, his days in internment camp, and his subsequent involvement in many community-related activities. As he told these stories, his passion for life, his strong sense of history, and his vision for the future of JAMsj was crystal clear.Eiichi Sakauye was born in San Jose, California, on January 25, 1912, the eldest of seven children. He grew up on the farm that his father, Yuwakichi, purchased in 1907, prior to the Alien Land Law of 1913. Eiichi spent his entire life on that farm except his 1942-1945 incarceration at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, internment camp.

I first got to know Eiichi when I spent several days with him while preparing for an extensive interview with him that was to be a part of a video history project. Our friendship blossomed when, at age 90, he decided that his night vision was not good enough to drive after dark. This decision resulted in my routinely picking him up to attend JAMsj board meetings and other evening events. During this period, I had the privilege of listening to many stories about his fascinating life--from his childhood, his days in internment camp, and his subsequent involvement in many community-related activities. As he told these stories, his passion for life, his strong sense of history, and his vision for the future of JAMsj was crystal clear.Eiichi Sakauye was born in San Jose, California, on January 25, 1912, the eldest of seven children. He grew up on the farm that his father, Yuwakichi, purchased in 1907, prior to the Alien Land Law of 1913. Eiichi spent his entire life on that farm except his 1942-1945 incarceration at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, internment camp. Despite the busy times, he learned much about farming, business transactions, and interacting with others. Eiichi also demonstrated great ingenuity and resourcefulness during this early period on the farm. When he and his brother could not get anyone to construct a pear-sorting machine, they had the necessary parts fabricated and assembled the machine themselves.At the outbreak of WWII, Eiichi was 29 years old, a seasoned farmer, an employer, and a community leader. He recalled the shock of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent flurry of activity preparing to leave the farm for some unknown destination. Neighbors and friends who did not own their own homes were allowed to store their belongings on Eiichi’s property during the internment.Eiichi developed a special relationship with one particular neighbor, Edward Seely. When Eiichi's family was evacuated, Edward volunteered to look after the Sakauye farm. Ironically, Eiichi’s family had looked after the Seely’s farm, as well as his invalid mother, while Edward served in the military during WWI. When Eiichi returned from camp after four years, everything was just as he had left it, thanks to the Seelys’ protective guardianship. Eiichi paid tribute to Edward Seely long after his friend's death by placing flowers on Edward's grave every week.

Despite the busy times, he learned much about farming, business transactions, and interacting with others. Eiichi also demonstrated great ingenuity and resourcefulness during this early period on the farm. When he and his brother could not get anyone to construct a pear-sorting machine, they had the necessary parts fabricated and assembled the machine themselves.At the outbreak of WWII, Eiichi was 29 years old, a seasoned farmer, an employer, and a community leader. He recalled the shock of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent flurry of activity preparing to leave the farm for some unknown destination. Neighbors and friends who did not own their own homes were allowed to store their belongings on Eiichi’s property during the internment.Eiichi developed a special relationship with one particular neighbor, Edward Seely. When Eiichi's family was evacuated, Edward volunteered to look after the Sakauye farm. Ironically, Eiichi’s family had looked after the Seely’s farm, as well as his invalid mother, while Edward served in the military during WWI. When Eiichi returned from camp after four years, everything was just as he had left it, thanks to the Seelys’ protective guardianship. Eiichi paid tribute to Edward Seely long after his friend's death by placing flowers on Edward's grave every week. Eiichi held several jobs in Heart Mountain, including block manager and activities coordinator. In addition, because of his extended farming background, Eiichi was assigned to be the assistant superintendent of agriculture. He recognized the severity of the weather conditions in Wyoming, including the short growing season, scarcity of water, and lack of nutrients in the soil.He recruited fellow internee farmers and others who had knowledge about soil engineering, irrigation, fertilizer, seeds, and other specialties to determine what kind of farming made sense in the barren surroundings. After many brainstorming sessions, they settled on the best approach and established a flourishing farm system that produced a wide variety of produce. An example of their labors was, daikon (Japanese turnip), foreign to Wyoming.

Eiichi held several jobs in Heart Mountain, including block manager and activities coordinator. In addition, because of his extended farming background, Eiichi was assigned to be the assistant superintendent of agriculture. He recognized the severity of the weather conditions in Wyoming, including the short growing season, scarcity of water, and lack of nutrients in the soil.He recruited fellow internee farmers and others who had knowledge about soil engineering, irrigation, fertilizer, seeds, and other specialties to determine what kind of farming made sense in the barren surroundings. After many brainstorming sessions, they settled on the best approach and established a flourishing farm system that produced a wide variety of produce. An example of their labors was, daikon (Japanese turnip), foreign to Wyoming. After the war, Eiichi returned to his San Jose farm. Similar to the story of Ulysses returning home, Eiichi recalled that his dog, left behind during the long incarceration, still recognized him. At first, the dog approached him cautiously and with a growl, then broke into a run, wagging his tail madly, so happy was he to see his owner again.After his return to San Jose, Eiichi was sought by many organizations. His passion for history, love of education and his sense of civic responsibility got him involved with many organizations: the Santa Clara Historical Commission, San Jose Museum of Art, Preservation Action Council, Milpitas Historical Museum, Jefferson School Board, Santa Clara Unified School District Board, Agricultural Commission, and Valley Water District.His ethnic pride moved him to become a founding member of the Loyalty League of Sa

After the war, Eiichi returned to his San Jose farm. Similar to the story of Ulysses returning home, Eiichi recalled that his dog, left behind during the long incarceration, still recognized him. At first, the dog approached him cautiously and with a growl, then broke into a run, wagging his tail madly, so happy was he to see his owner again.After his return to San Jose, Eiichi was sought by many organizations. His passion for history, love of education and his sense of civic responsibility got him involved with many organizations: the Santa Clara Historical Commission, San Jose Museum of Art, Preservation Action Council, Milpitas Historical Museum, Jefferson School Board, Santa Clara Unified School District Board, Agricultural Commission, and Valley Water District.His ethnic pride moved him to become a founding member of the Loyalty League of Sa n Jose, now known as the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL),as well as a strong supporter of both the Yu-Ai Kai Senior Center and the Japanese American National Museum (JANM). Using his private collection of photos and movies, as well as relying on his vivid memories, Eiichi authored a seminal book, Heart Mountain: A Photo Essay. Eiichi and others founded the Japanese American Resource Center (JARC) in 1987. JARC’s goal was to preserve this area's Japanese American history so subsequent generations of Sansei and Yonsei could learn from and take pride in their heritage. In the early 1990s, JARC was housed in the Issei Memorial Building. But Eiichi saw the need for a larger venue to display photos, stories, and artifacts.One of Eiichi’s friends was Dr. Tokio Ishikawa, noted physician and Japantown historian. When Dr. Ishikawa moved, his North Fifth Street residence became available for sale. Eiichi discussed purchasing the property to become a JARC museum with Dr. Ishikawa, who was delighted with the idea of his home becoming a community resource.With the purchase completed in 1998, Eiichi generously donated the property to JARC, allowing it to become the new home for the museum. JARC subsequently changed its name to the Japanese American Museum of San Jose (JAMsj). Clearly, without Eiichi’s vision, foresight, leadership, and strong financial support, JAMsj would not be where it is today.---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------