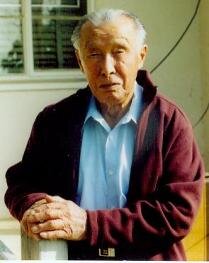

By Joe Yasutake I first got to know Eiichi when I spent several days with him while preparing for an extensive interview with him that was to be a part of a video history project. Our friendship blossomed when, at age 90, he decided that his night vision was not good enough to drive after dark. This decision resulted in my routinely picking him up to attend JAMsj board meetings and other evening events. During this period, I had the privilege of listening to many stories about his fascinating life--from his childhood, his days in internment camp, and his subsequent involvement in many community-related activities. As he told these stories, his passion for life, his strong sense of history, and his vision for the future of JAMsj was crystal clear.Eiichi Sakauye was born in San Jose, California, on January 25, 1912, the eldest of seven children. He grew up on the farm that his father, Yuwakichi, purchased in 1907, prior to the Alien Land Law of 1913. Eiichi spent his entire life on that farm except his 1942-1945 incarceration at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, internment camp.

I first got to know Eiichi when I spent several days with him while preparing for an extensive interview with him that was to be a part of a video history project. Our friendship blossomed when, at age 90, he decided that his night vision was not good enough to drive after dark. This decision resulted in my routinely picking him up to attend JAMsj board meetings and other evening events. During this period, I had the privilege of listening to many stories about his fascinating life--from his childhood, his days in internment camp, and his subsequent involvement in many community-related activities. As he told these stories, his passion for life, his strong sense of history, and his vision for the future of JAMsj was crystal clear.Eiichi Sakauye was born in San Jose, California, on January 25, 1912, the eldest of seven children. He grew up on the farm that his father, Yuwakichi, purchased in 1907, prior to the Alien Land Law of 1913. Eiichi spent his entire life on that farm except his 1942-1945 incarceration at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, internment camp. Despite the busy times, he learned much about farming, business transactions, and interacting with others. Eiichi also demonstrated great ingenuity and resourcefulness during this early period on the farm. When he and his brother could not get anyone to construct a pear-sorting machine, they had the necessary parts fabricated and assembled the machine themselves.At the outbreak of WWII, Eiichi was 29 years old, a seasoned farmer, an employer, and a community leader. He recalled the shock of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent flurry of activity preparing to leave the farm for some unknown destination. Neighbors and friends who did not own their own homes were allowed to store their belongings on Eiichi’s property during the internment.Eiichi developed a special relationship with one particular neighbor, Edward Seely. When Eiichi's family was evacuated, Edward volunteered to look after the Sakauye farm. Ironically, Eiichi’s family had looked after the Seely’s farm, as well as his invalid mother, while Edward served in the military during WWI. When Eiichi returned from camp after four years, everything was just as he had left it, thanks to the Seelys’ protective guardianship. Eiichi paid tribute to Edward Seely long after his friend's death by placing flowers on Edward's grave every week.

Despite the busy times, he learned much about farming, business transactions, and interacting with others. Eiichi also demonstrated great ingenuity and resourcefulness during this early period on the farm. When he and his brother could not get anyone to construct a pear-sorting machine, they had the necessary parts fabricated and assembled the machine themselves.At the outbreak of WWII, Eiichi was 29 years old, a seasoned farmer, an employer, and a community leader. He recalled the shock of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent flurry of activity preparing to leave the farm for some unknown destination. Neighbors and friends who did not own their own homes were allowed to store their belongings on Eiichi’s property during the internment.Eiichi developed a special relationship with one particular neighbor, Edward Seely. When Eiichi's family was evacuated, Edward volunteered to look after the Sakauye farm. Ironically, Eiichi’s family had looked after the Seely’s farm, as well as his invalid mother, while Edward served in the military during WWI. When Eiichi returned from camp after four years, everything was just as he had left it, thanks to the Seelys’ protective guardianship. Eiichi paid tribute to Edward Seely long after his friend's death by placing flowers on Edward's grave every week. Eiichi held several jobs in Heart Mountain, including block manager and activities coordinator. In addition, because of his extended farming background, Eiichi was assigned to be the assistant superintendent of agriculture. He recognized the severity of the weather conditions in Wyoming, including the short growing season, scarcity of water, and lack of nutrients in the soil.He recruited fellow internee farmers and others who had knowledge about soil engineering, irrigation, fertilizer, seeds, and other specialties to determine what kind of farming made sense in the barren surroundings. After many brainstorming sessions, they settled on the best approach and established a flourishing farm system that produced a wide variety of produce. An example of their labors was, daikon (Japanese turnip), foreign to Wyoming.

Eiichi held several jobs in Heart Mountain, including block manager and activities coordinator. In addition, because of his extended farming background, Eiichi was assigned to be the assistant superintendent of agriculture. He recognized the severity of the weather conditions in Wyoming, including the short growing season, scarcity of water, and lack of nutrients in the soil.He recruited fellow internee farmers and others who had knowledge about soil engineering, irrigation, fertilizer, seeds, and other specialties to determine what kind of farming made sense in the barren surroundings. After many brainstorming sessions, they settled on the best approach and established a flourishing farm system that produced a wide variety of produce. An example of their labors was, daikon (Japanese turnip), foreign to Wyoming. After the war, Eiichi returned to his San Jose farm. Similar to the story of Ulysses returning home, Eiichi recalled that his dog, left behind during the long incarceration, still recognized him. At first, the dog approached him cautiously and with a growl, then broke into a run, wagging his tail madly, so happy was he to see his owner again.After his return to San Jose, Eiichi was sought by many organizations. His passion for history, love of education and his sense of civic responsibility got him involved with many organizations: the Santa Clara Historical Commission, San Jose Museum of Art, Preservation Action Council, Milpitas Historical Museum, Jefferson School Board, Santa Clara Unified School District Board, Agricultural Commission, and Valley Water District.His ethnic pride moved him to become a founding member of the Loyalty League of Sa

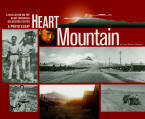

After the war, Eiichi returned to his San Jose farm. Similar to the story of Ulysses returning home, Eiichi recalled that his dog, left behind during the long incarceration, still recognized him. At first, the dog approached him cautiously and with a growl, then broke into a run, wagging his tail madly, so happy was he to see his owner again.After his return to San Jose, Eiichi was sought by many organizations. His passion for history, love of education and his sense of civic responsibility got him involved with many organizations: the Santa Clara Historical Commission, San Jose Museum of Art, Preservation Action Council, Milpitas Historical Museum, Jefferson School Board, Santa Clara Unified School District Board, Agricultural Commission, and Valley Water District.His ethnic pride moved him to become a founding member of the Loyalty League of Sa n Jose, now known as the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL),as well as a strong supporter of both the Yu-Ai Kai Senior Center and the Japanese American National Museum (JANM). Using his private collection of photos and movies, as well as relying on his vivid memories, Eiichi authored a seminal book, Heart Mountain: A Photo Essay. Eiichi and others founded the Japanese American Resource Center (JARC) in 1987. JARC’s goal was to preserve this area's Japanese American history so subsequent generations of Sansei and Yonsei could learn from and take pride in their heritage. In the early 1990s, JARC was housed in the Issei Memorial Building. But Eiichi saw the need for a larger venue to display photos, stories, and artifacts.One of Eiichi’s friends was Dr. Tokio Ishikawa, noted physician and Japantown historian. When Dr. Ishikawa moved, his North Fifth Street residence became available for sale. Eiichi discussed purchasing the property to become a JARC museum with Dr. Ishikawa, who was delighted with the idea of his home becoming a community resource.With the purchase completed in 1998, Eiichi generously donated the property to JARC, allowing it to become the new home for the museum. JARC subsequently changed its name to the Japanese American Museum of San Jose (JAMsj). Clearly, without Eiichi’s vision, foresight, leadership, and strong financial support, JAMsj would not be where it is today.---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

n Jose, now known as the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL),as well as a strong supporter of both the Yu-Ai Kai Senior Center and the Japanese American National Museum (JANM). Using his private collection of photos and movies, as well as relying on his vivid memories, Eiichi authored a seminal book, Heart Mountain: A Photo Essay. Eiichi and others founded the Japanese American Resource Center (JARC) in 1987. JARC’s goal was to preserve this area's Japanese American history so subsequent generations of Sansei and Yonsei could learn from and take pride in their heritage. In the early 1990s, JARC was housed in the Issei Memorial Building. But Eiichi saw the need for a larger venue to display photos, stories, and artifacts.One of Eiichi’s friends was Dr. Tokio Ishikawa, noted physician and Japantown historian. When Dr. Ishikawa moved, his North Fifth Street residence became available for sale. Eiichi discussed purchasing the property to become a JARC museum with Dr. Ishikawa, who was delighted with the idea of his home becoming a community resource.With the purchase completed in 1998, Eiichi generously donated the property to JARC, allowing it to become the new home for the museum. JARC subsequently changed its name to the Japanese American Museum of San Jose (JAMsj). Clearly, without Eiichi’s vision, foresight, leadership, and strong financial support, JAMsj would not be where it is today.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- After World War II, Eiichi Sakauye married Susuye Wakano. They had two daughters, Carolyn and Jane. After Susuye’s passing, Eiichi married Marie Kawasak, who still resides on the farm. The Sakauye Family farm is one of the few farms still operating in Silicon Valley.

After World War II, Eiichi Sakauye married Susuye Wakano. They had two daughters, Carolyn and Jane. After Susuye’s passing, Eiichi married Marie Kawasak, who still resides on the farm. The Sakauye Family farm is one of the few farms still operating in Silicon Valley.