The following article was written by JAMsj docent, Will Kaku. He reflects on the Chizuko Judy Sugita de Queiroz’ Camp Days 1942-1945 exhibit. The exhibit will be closing on December 30, 2011.

The Emotional Journey into Camp Days

By Will Kaku

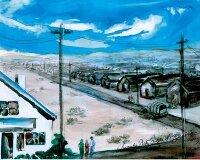

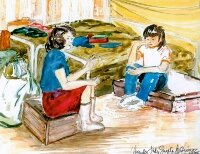

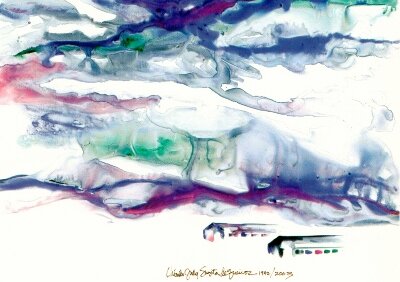

When the JAMsj reopened in October 2010, I used to start my tours like many docents do: in chronological order starting with the story of Chinese and Japanese immigration, the insatiable appetite for cheap labor by agribusiness and industrialists, the impact of racial attitudes and anti-Asian exclusionary laws, and the transition of an immigrant population from a “bachelor society” to one of permanence in San Jose’s Japantown. To me, to start from the beginning was the only way to tell this story.That is how many of us learned history in school. We were often immersed in historical timelines, the identification of key events, influential innovations, political leaders and movements, and the study of causality. There were many facts that had to be understood, necessitating a firm grasp on the “who, what, why, when, and where” of history.When it came to Chizuko Judy Sugita de Quieroz’ watercolor art exhibit, Camp Days 1942-1945, it just didn’t seem to fit my linearly constructed, fact-driven narrative. I often concluded my tours informing my tour group that we also had an art exhibit room which they could walk through and enjoy at their own leisure.I just didn’t get it. I simply saw that there were brightly colored images on the exhibit walls that depicted slices of camp life. There didn’t seem to be any sense of connectivity and profundity, and it missed the opportunity to make an overt political statement. There were also several paintings done in a child-like manner. I could probably paint better than that, I thought.During my breaks, I used to sit and relax in the Camp Days exhibit room, enjoying quiet, introspective times. Letting my mind wander into Chizuko’s paintings, I would reflect on the many former internees that I had met. And eventually, I started to understand.Sometimes the appreciation of art is like that. Like a fine wine, you often can’t appreciate it until you are fully aware of its subtle complexity. You cannot viscerally connect to the work until you are able to unlock the deeply embedded emotional layers. Chizuko’s exhibit describes a young girl’s journey into womanhood and reveals a deeply personal, emotionally scarring reaction to internment, a reaction that many former internees can identify with. For many in the Japanese American community, the repercussions of internment define who we are, shaping our values, political beliefs, and emotional character.In Chizuko’s work, there are basically two major styles represented in the exhibit: a representational form and an abstract form that embeds impressionistic components. Many of the representational forms are painted in a child-like manner, although it would be more accurate to say that they are painted through the eyes of a young Chizuko and layered with the knowledge of what was yet to come from the adult Chizuko.Chizuko had the most difficult time trying to create the abstract forms. Many of these paintings are heavily textured with deep emotions that include sorrow, loneliness, loss, and longing.

When the JAMsj reopened in October 2010, I used to start my tours like many docents do: in chronological order starting with the story of Chinese and Japanese immigration, the insatiable appetite for cheap labor by agribusiness and industrialists, the impact of racial attitudes and anti-Asian exclusionary laws, and the transition of an immigrant population from a “bachelor society” to one of permanence in San Jose’s Japantown. To me, to start from the beginning was the only way to tell this story.That is how many of us learned history in school. We were often immersed in historical timelines, the identification of key events, influential innovations, political leaders and movements, and the study of causality. There were many facts that had to be understood, necessitating a firm grasp on the “who, what, why, when, and where” of history.When it came to Chizuko Judy Sugita de Quieroz’ watercolor art exhibit, Camp Days 1942-1945, it just didn’t seem to fit my linearly constructed, fact-driven narrative. I often concluded my tours informing my tour group that we also had an art exhibit room which they could walk through and enjoy at their own leisure.I just didn’t get it. I simply saw that there were brightly colored images on the exhibit walls that depicted slices of camp life. There didn’t seem to be any sense of connectivity and profundity, and it missed the opportunity to make an overt political statement. There were also several paintings done in a child-like manner. I could probably paint better than that, I thought.During my breaks, I used to sit and relax in the Camp Days exhibit room, enjoying quiet, introspective times. Letting my mind wander into Chizuko’s paintings, I would reflect on the many former internees that I had met. And eventually, I started to understand.Sometimes the appreciation of art is like that. Like a fine wine, you often can’t appreciate it until you are fully aware of its subtle complexity. You cannot viscerally connect to the work until you are able to unlock the deeply embedded emotional layers. Chizuko’s exhibit describes a young girl’s journey into womanhood and reveals a deeply personal, emotionally scarring reaction to internment, a reaction that many former internees can identify with. For many in the Japanese American community, the repercussions of internment define who we are, shaping our values, political beliefs, and emotional character.In Chizuko’s work, there are basically two major styles represented in the exhibit: a representational form and an abstract form that embeds impressionistic components. Many of the representational forms are painted in a child-like manner, although it would be more accurate to say that they are painted through the eyes of a young Chizuko and layered with the knowledge of what was yet to come from the adult Chizuko.Chizuko had the most difficult time trying to create the abstract forms. Many of these paintings are heavily textured with deep emotions that include sorrow, loneliness, loss, and longing.

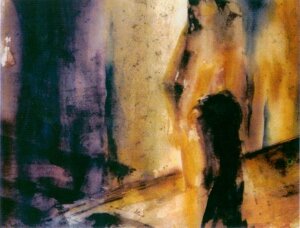

Uncertain Future depicts Chizuko’s family looking far off into the distance, contemplating what their future holds for them when they are finally released from the camp. Many people had great difficulty trying to recover their lives, and some encountered hostile reactions from their former communities. I once met Miyo Uzaki, a former internee, who told me that when she returned to her church in the Fresno area after the war, the pastor of her church informed her that he and the congregation did not want her family to return to the church. JAMsj curator, Jimi Yamaichi, remembered, “When we tried to move into our new home, the neighbors took a vote. We barely got in on a vote of 7 to 6.” Unanswered Prayers covers several major themes that flow throughout Camp Days. In camp, young Chizuko is told that, “If you pray hard enough, your prayers will come true.” Chizuko remarks, “Camp made me realize that my prayers would never be answered. I knew my mother would never come back to life, and I would never be a blue-eyed blond.” This idealized longing for a mother she never knew —she passed away when Chizuko was a baby – is captured in other images in the exhibit. Chizuko states, “Being motherless in camp had a detrimental impact on my childhood. I didn't have anyone. If I had a mother, I'm sure that she would have protected me and taken me every place with her. I wouldn't have had any traumatic experiences”“That painting is an abstract of me,” Chizuko told me. “I’m coming out of the cement shower room, so uncomfortable, sad, and depressed.” The naked body of Chizuko suggests great vulnerability, loneliness, and insecurity. Without her mother, the young Chizuko was becoming increasingly insecure about her body as she moved toward puberty. The lack of privacy in camp also made her feel extremely uncomfortable. Chizuko explained, “I was always embarrassed to shower with a lot of naked women.” In one painting, It’s Not Polite to Stare, she was told that she couldn’t play with her classmates because she had no mother and that she was rude because she stared at another woman in the shower.Her prayer to be non-Japanese in appearance obviously means that she would not have to be in camp if she were a “blue-eyed blond.” But, the wish also carries a deeper implication in the rejection of one’s self. Many of us who grew up in an exclusively Caucasian environment -- in a time when no Asian faces were represented on TV, in films , toys, commercials or magazines -- have harbored similar feelings of “wanting to be white” or a disdain and rejection of everything that was Japanese within ourselves.Other paintings in the exhibit convey similar themes. A Good American, Black and White Houses, Discovery and Disillusionment, and No Japs Allowed, reinforce her feeling of being a “bad person” and reveal her painful reaction to ostracism and discrimination.

Unanswered Prayers covers several major themes that flow throughout Camp Days. In camp, young Chizuko is told that, “If you pray hard enough, your prayers will come true.” Chizuko remarks, “Camp made me realize that my prayers would never be answered. I knew my mother would never come back to life, and I would never be a blue-eyed blond.” This idealized longing for a mother she never knew —she passed away when Chizuko was a baby – is captured in other images in the exhibit. Chizuko states, “Being motherless in camp had a detrimental impact on my childhood. I didn't have anyone. If I had a mother, I'm sure that she would have protected me and taken me every place with her. I wouldn't have had any traumatic experiences”“That painting is an abstract of me,” Chizuko told me. “I’m coming out of the cement shower room, so uncomfortable, sad, and depressed.” The naked body of Chizuko suggests great vulnerability, loneliness, and insecurity. Without her mother, the young Chizuko was becoming increasingly insecure about her body as she moved toward puberty. The lack of privacy in camp also made her feel extremely uncomfortable. Chizuko explained, “I was always embarrassed to shower with a lot of naked women.” In one painting, It’s Not Polite to Stare, she was told that she couldn’t play with her classmates because she had no mother and that she was rude because she stared at another woman in the shower.Her prayer to be non-Japanese in appearance obviously means that she would not have to be in camp if she were a “blue-eyed blond.” But, the wish also carries a deeper implication in the rejection of one’s self. Many of us who grew up in an exclusively Caucasian environment -- in a time when no Asian faces were represented on TV, in films , toys, commercials or magazines -- have harbored similar feelings of “wanting to be white” or a disdain and rejection of everything that was Japanese within ourselves.Other paintings in the exhibit convey similar themes. A Good American, Black and White Houses, Discovery and Disillusionment, and No Japs Allowed, reinforce her feeling of being a “bad person” and reveal her painful reaction to ostracism and discrimination.

When Chizuko speaks about Camp Days, it often leads to tears. Many of her emotions have been bottled up and suppressed over the years. Chizuko suffered great loneliness in camp. Her older siblings told her to just deal with her situation, saying “You’re not a baby anymore.” Much later in life, when she would bring up the topic of camp or her mother, “My brothers and sisters would just say that I just cried and whined all the time and that would end the conversation,” Chizuko explained.Chizuko now says that producing this exhibit was a cathartic experience for her. She normally paints outdoors, but when she painted Camp Days, she isolated herself in a room, revisiting many of the painful memories. All of the emotions that had been previously submerged and invalidated by others could no longer be held back. “I did a lot of gnashing of teeth, crying, laughing, while just remembering more and more details,” Chizuko recalled.The personal, emotional reaction to historical events is one that many people can identify with. During the hearings on redress in the 1980s, many people remember the sudden outpouring of long-held emotions. The emotional repercussions of internment define who many of us are as individuals and as a community. Armed with this deeper knowledge of Camp Days, the life of Chizuko Judy Sugita de Queiroz, and stories from many of the former internees that I have met, I now start rather than end my tours in the Camp Days exhibit. I am very thankful to have taken this emotional journey with Chizuko into Camp Days. This journey will remain with me for a long time.

To get more information from the artist, visit www.artbychiz.com.------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------