Imagine visiting one of the World War II American concentration camps and actually being able to see what it looked like when Japanese Americans were incarcerated there. Modern technology and the hard work of various organizations will soon make this possible. A good example of the former is CyArk, a non-profit organization dedicated to the digital preservation of cultural heritage sites. CyArk’s work in digitally reconstructing the Manzanar, Topaz, and Tule Lake Wartime Relocation Authority (WRA) camps, together with the development of a “demonstration block” at Manzanar, will allow visitors to be part of both virtual and physical realities.Although some of this is still a work in progress, the Manzanar National Historic Site is already well worth a visit. In addition to the demonstration block, which today includes a mess hall and two barracks, there is a lot to see: a very impressive interpretive center, rotating exhibits, and quality public programs. In addition, helpful park rangers are on site. The interpretive display inside of the mess hall is already open to the public. In addition, visitors can walk through the barracks to get a feel for things to come.

Imagine visiting one of the World War II American concentration camps and actually being able to see what it looked like when Japanese Americans were incarcerated there. Modern technology and the hard work of various organizations will soon make this possible. A good example of the former is CyArk, a non-profit organization dedicated to the digital preservation of cultural heritage sites. CyArk’s work in digitally reconstructing the Manzanar, Topaz, and Tule Lake Wartime Relocation Authority (WRA) camps, together with the development of a “demonstration block” at Manzanar, will allow visitors to be part of both virtual and physical realities.Although some of this is still a work in progress, the Manzanar National Historic Site is already well worth a visit. In addition to the demonstration block, which today includes a mess hall and two barracks, there is a lot to see: a very impressive interpretive center, rotating exhibits, and quality public programs. In addition, helpful park rangers are on site. The interpretive display inside of the mess hall is already open to the public. In addition, visitors can walk through the barracks to get a feel for things to come.

CYARK

Cyark’s work in digitally reconstructing Manzanar (circa 1944) is part of an exciting, larger project, the Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. Cyark is working on this project in collaboration with the National Park Service (NPS), Manzanar National Historic Site, Tule Lake Unit of the WWII Valor in the Pacific National Monument, and Topaz Museum.Elizabeth Lee, CyArk’s Director of Operations, was interviewed by Manzanar Committee blogger Gann Matsuda last year after a preview/feedback session in Los Angeles. Lee described the project as “going beyond just capturing the physical remains at the site, of which, there are very few.” She went on to say that, “Using that as a foundation, and combining that with historic resources, such as maps, photographs, and even oral histories, we can virtually reconstruct the site in 3D, and in an immersive, interactive environment.”The first step of Cyark’s work uses laser scan data that is collected at each site, GPS, and photography to accurately capture the sites and their landscape in 3D. Coupled with historic documentation such as architectural drawings, photographs, and archival research, CyArk is able to develop a virtual recreation of the site. For example, although today Merritt Park at Manzanar is arid and dusty, the virtual recreation shows the park as it was in 1944, including the waterfall that connected the two ponds and the famous wild rose bushes grafted by Kuichiro Nishi. Visitors will even be able to hear the sound of the waterfall. A video preview of the Merritt Park reconstruction can be found on CyArk’s Virtual Manzanar blog. Parks and gardens are not the only things captured in this project. A large portion of the entire site, including the barracks (both interior and exterior), is also included. The high-tech computer generated imagery (cgi) videos, coupled with oral histories featuring former prisoners and historic images, provide a unique opportunity to experience what life was like for the Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in these WRA camps.Not only will those interested be able to visit these camps virtually via the Internet, but also visitors will be able to experience an “augmented reality” through the use of smart phones or tablets. The vision is for visitors to be able to see not just the reality of a site in front of them today (for example, the dry and arid Merritt Park), but also see on their devices the digitally reconstructed image of what that exact same view might have looked like in 1944. When visitors move, the view on the device would move with them. Lee described this as “a window into time, looking back some sixty years.”Gann Matsuda’s full-length blog, detailing this very interesting project, "Interactive 3D Model Could Revolutionize Real and Virtual Visitor Experience For Manzanar," can be found on the Manzanar Committee’s website.For more information about our upcoming March 16 presentation by CyArk, please contact Komo at PublicPrograms@JAMsj.org. A full announcement will appear in next month’s edition of the JAMsj E-News.

Parks and gardens are not the only things captured in this project. A large portion of the entire site, including the barracks (both interior and exterior), is also included. The high-tech computer generated imagery (cgi) videos, coupled with oral histories featuring former prisoners and historic images, provide a unique opportunity to experience what life was like for the Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in these WRA camps.Not only will those interested be able to visit these camps virtually via the Internet, but also visitors will be able to experience an “augmented reality” through the use of smart phones or tablets. The vision is for visitors to be able to see not just the reality of a site in front of them today (for example, the dry and arid Merritt Park), but also see on their devices the digitally reconstructed image of what that exact same view might have looked like in 1944. When visitors move, the view on the device would move with them. Lee described this as “a window into time, looking back some sixty years.”Gann Matsuda’s full-length blog, detailing this very interesting project, "Interactive 3D Model Could Revolutionize Real and Virtual Visitor Experience For Manzanar," can be found on the Manzanar Committee’s website.For more information about our upcoming March 16 presentation by CyArk, please contact Komo at PublicPrograms@JAMsj.org. A full announcement will appear in next month’s edition of the JAMsj E-News.

DEMONSTRATION BLOCK AT MANZANAR

The Manzanar War Relocation Center confined more than 10,000 Japanese Americans in 36 blocks from 1942 to 1945. Each block included 14 barracks buildings, a mess hall, a recreation building, latrines, and laundry and ironing rooms. After the war, the buildings were sold for scrap lumber or relocated. A visit to the site will quickly show how barren it is today. Thanks to an ambitious project to develop a “demonstration block” that interprets daily life in the camp, visitors will be able to get a glimpse of life was like for Japanese Americans who were unjustly incarcerated during World War II.So far, a mess hall and two barracks have been constructed in Block 14. In addition, the design work for four utility buildings has already been completed. Friends of Manzanar, a nonprofit partner of the NPS, continues to raise funds to support the development and interpretation of Block 14.

The Manzanar War Relocation Center confined more than 10,000 Japanese Americans in 36 blocks from 1942 to 1945. Each block included 14 barracks buildings, a mess hall, a recreation building, latrines, and laundry and ironing rooms. After the war, the buildings were sold for scrap lumber or relocated. A visit to the site will quickly show how barren it is today. Thanks to an ambitious project to develop a “demonstration block” that interprets daily life in the camp, visitors will be able to get a glimpse of life was like for Japanese Americans who were unjustly incarcerated during World War II.So far, a mess hall and two barracks have been constructed in Block 14. In addition, the design work for four utility buildings has already been completed. Friends of Manzanar, a nonprofit partner of the NPS, continues to raise funds to support the development and interpretation of Block 14. The project was approved in 1997, after consultation with the Manzanar Advisory Commission, former internees, and historians. The first physical element of the reconstruction was the World War II-era mess hall. In December 2002, after a period of negotiation with Inyo County, it was delivered by truck in four sections from the Bishop airport. Although this mess hall was not at Manzanar during World War II, it was constructed during the same period from essentially the same mess hall plans used at Manzanar. Eventually, NPS received funding to restore the building to its 1942 appearance and to develop exhibits.

The project was approved in 1997, after consultation with the Manzanar Advisory Commission, former internees, and historians. The first physical element of the reconstruction was the World War II-era mess hall. In December 2002, after a period of negotiation with Inyo County, it was delivered by truck in four sections from the Bishop airport. Although this mess hall was not at Manzanar during World War II, it was constructed during the same period from essentially the same mess hall plans used at Manzanar. Eventually, NPS received funding to restore the building to its 1942 appearance and to develop exhibits. Park staff worked with Krister Olmon, Harvest Moon Studio, and Color-Ad Exhibits and Signage to create the exhibit, with research support from Friends of Manzanar. Opened in 2011, this restoration is a wonderful exhibit, reflecting what life was like in the WRA camps and emphasizing the central importance of the mess hall. The installation includes historic photos, articles, and quotes, as well as period items chosen to reflect what might have been found in the mess hall during that time.In its January 2011 press release, NPS Superintendent Les Inafuku described his experience saying, "As I walk through the mess hall, I find myself imagining that I've walked in right at the busiest moment of a meal and that I'd better be careful not to bump into a cook or dish washer. My great thanks go out to the former internees who provided us with the fine details about meals and the mess halls, plus the countless hours that our Manzanar staff and our creative and dedicated exhibit designers and fabricators devoted to research, develop concepts of, and produce the exhibits."

Park staff worked with Krister Olmon, Harvest Moon Studio, and Color-Ad Exhibits and Signage to create the exhibit, with research support from Friends of Manzanar. Opened in 2011, this restoration is a wonderful exhibit, reflecting what life was like in the WRA camps and emphasizing the central importance of the mess hall. The installation includes historic photos, articles, and quotes, as well as period items chosen to reflect what might have been found in the mess hall during that time.In its January 2011 press release, NPS Superintendent Les Inafuku described his experience saying, "As I walk through the mess hall, I find myself imagining that I've walked in right at the busiest moment of a meal and that I'd better be careful not to bump into a cook or dish washer. My great thanks go out to the former internees who provided us with the fine details about meals and the mess halls, plus the countless hours that our Manzanar staff and our creative and dedicated exhibit designers and fabricators devoted to research, develop concepts of, and produce the exhibits." Dick Mansfield, a Friends of Manzanar director and the organization’s treasurer, says there are currently two primary Block 14 projects, both still in the planning stages, under way:

Dick Mansfield, a Friends of Manzanar director and the organization’s treasurer, says there are currently two primary Block 14 projects, both still in the planning stages, under way:

- Development and installation of interpretive materials within reconstructed Barracks 1 and 8

- Reconstruction and interpretation of the four central utility buildings--the men’s and women’s latrines, the laundry room, and the ironing room

The interpretive materials for Barracks 1 and 8 are fully funded, planning is nearly completed, and the installation is expected by late 2013 or early 2014. Detailed plans for the four central utility buildings have been drafted, but the project is still in the funding stage. Friends of Manzanar, which has undertaken to provide funding for the central utility building project, has an anticipated budget of $1 million. In the fiscal year 2009 to 2010, Congress approved funding, proposed by California Senator Diane Feinstein, for reconstructing Barracks 1 and 8 on Block 14. The barracks have been open to visitors for more than a year and a half, although the interpretive work in the two buildings is still in progress. Barracks 1 reflects what it would have been like when Japanese Americans first arrived at Manzanar in 1942, while Barracks 8 reflects life in 1945. A visitor viewing the site today can walk through the buildings and see the difference. Barracks 1 has wooden planks, complete with gaps, and no wall covering. In Barracks 8, the planks are covered with linoleum flooring.

In the fiscal year 2009 to 2010, Congress approved funding, proposed by California Senator Diane Feinstein, for reconstructing Barracks 1 and 8 on Block 14. The barracks have been open to visitors for more than a year and a half, although the interpretive work in the two buildings is still in progress. Barracks 1 reflects what it would have been like when Japanese Americans first arrived at Manzanar in 1942, while Barracks 8 reflects life in 1945. A visitor viewing the site today can walk through the buildings and see the difference. Barracks 1 has wooden planks, complete with gaps, and no wall covering. In Barracks 8, the planks are covered with linoleum flooring. In the January 2010 NPS press release for the groundbreaking of the barracks, Superintendent Inafuku noted, “All Americans had to adapt during World War II, including Japanese Americans confined at Manzanar. Future visitors to Block 14 can learn how Japanese Americans lived at Manzanar and improved their living situations. Our elders can still inspire us to improve our lives and help shape our great nation.”

In the January 2010 NPS press release for the groundbreaking of the barracks, Superintendent Inafuku noted, “All Americans had to adapt during World War II, including Japanese Americans confined at Manzanar. Future visitors to Block 14 can learn how Japanese Americans lived at Manzanar and improved their living situations. Our elders can still inspire us to improve our lives and help shape our great nation.”

EXCAVATION OPPORTUNITIES

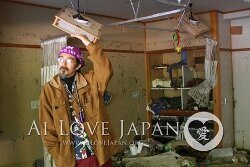

The NPS has offered opportunities for the general public to help with archeological digs at Manzanar for several years. Park Ranger Kristen Luetkemeier confirmed plans to offer this program again this summer. The three digs are led by noted confinement-sites archeologist Jeff Burton (jeff_burton@nps.gov), under whose direction many of the beautiful decorative gardens developed by the confined persons of Japanese ancestry during World War II have been excavated.A description of one of the 2012 digs states:Within Block 14 of the internee housing area, volunteers will search for a lost fish pond, investigate possible basements, excavate and restore other landscaping and barracks features, and rebuild a retaining wall next to a basketball court. Uncovering and restoring these will help increase visitor understanding of the internee experience, as well as protect these important historic resources. Volunteers will be digging with shovels and small hand tools, using wheelbarrows, mixing concrete, reconstructing landscape features, and screening sediments to retrieve artifacts.Last year, the NPS was able to accommodate up to 10 volunteers (15 years old and up) per day. Although some of the work may be physically demanding, a variety of tasks is offered each day, “to suit a variety of interests and energy levels.” Tasks in the past have included digging with shovels and small hand tools, raking, operating wheelbarrows, screening sediments to retrieve artifacts, note taking, filling out forms and labels, and using a metal detector. All NPS asks is that volunteers have an “interest in history and a willingness to get dirty.” Volunteers can work any number of days.Click here to read more about last year's digs.

SPECIAL EXHIBITS & PROGRAMS

The NPS offers great programs and special exhibits. One current exhibit features photos and stories from Twice Heroes: America’s Nisei Veterans of World War II and Korea by photographer/author Tom Graves. Featured among the selected portraits are familiar faces such as the late Senator Daniel Inouye and former U.S. Secretary of Transportation, Norman Mineta, as well as less familiar heroes. Each portrait is accompanied by a short yet insightful story about that person. This exhibit was unveiled at a special program held for Veterans’ Day and included a book talk with Graves.The five paragraphs on Inouye describe one of his many speaking engagements and ends with:Those seated near the podium could see him touch the gold star that hung on the sky blue ribbon around his neck. “As a politician, I have been honored many times,” he said. “To be honored by your brothers is the highest honor. When I wear this medal, I wear it on your behalf. There is no such thing as a one-man hero. I can think of at least a dozen men in my company who should be wearing this. The medals belong to you.” Another soldier’s story told of racism and ended with a note about how 442 soldiers received lesser medals than those of other units. The soldier felt that this was because Hawaii was not yet a state and had no congressman to push a Medal of Honor nomination. He went on to tell of how these veterans and widows were not compensated, saying that, “You cannot eat a Congressional Medal.”Twice Heroes book website

Another soldier’s story told of racism and ended with a note about how 442 soldiers received lesser medals than those of other units. The soldier felt that this was because Hawaii was not yet a state and had no congressman to push a Medal of Honor nomination. He went on to tell of how these veterans and widows were not compensated, saying that, “You cannot eat a Congressional Medal.”Twice Heroes book website

PILGRIMAGE

The annual pilgrimage to Manzanar is held every year on the last Saturday of April. The 2012 program included a keynote speech by noted author and scholar Dr. Mitchell T. Maki, an afternoon program at the Manzanar cemetery site featuring taiko, an interfaith service, and traditional ondo dancing In the evening, the popular Manzanar at Dusk program was held. More information on the 2013 pilgrimage will be available on the Manzanar Committee website as the date approaches.Links:http://blog.manzanarcommittee.org/2012/03/19/author-scholar-dr-mitchell-maki-to-keynote-43rd-annual-manzanar-pilgrimage-april-28-2012/http://blog.manzanarcommittee.org/2011/03/21/mako-nakagawa-to-keynote-42nd-annual-manzanar-pilgrimage/http://www.manzanarcommittee.org/The_Manzanar_Committee/Our_Pilgrimage.html

VISITING MANZANAR

In addition to the mess hall and two recently reconstructed barracks, the Manzanar’s Interpretive Center features extensive exhibits, audio-visual programs, and a bookstore. For people visiting the Manzanar National Historic Site, Dick Mansfield recommends starting at the interpretive center with the 22-minute film that shows every half hour. Next, look through the excellent exhibits and visit Block 14, which is just a few steps from the interpretive center. Lastly, drive the peripheral road and imagine what this 10,000-person holding facility on the edge of the desert must have been like for people who had been forced out of their Pacific Coast homes, without any semblance of due process, in 1942. He notes that the site will be even more meaningful to visitors as the planned development of Block 14 moves forward.Winter hours of operation are 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Manzanar is located at 5001 Hiway 395, six miles south of Independence and nine miles north of Lone Pine, California. Programs and exhibits are free and open to the public. For further information, please call (760) 878-2194 or visit the NPS website at www.nps.gov/manz.

Other prominent Americans also drew stark parallels with the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. Actor and activist,

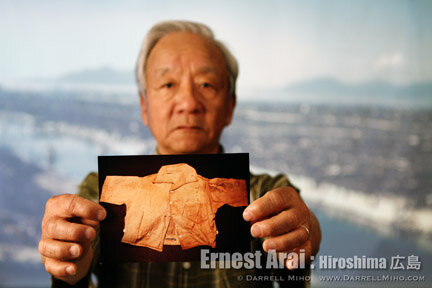

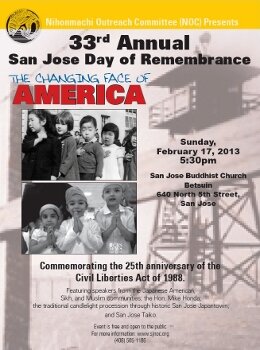

Other prominent Americans also drew stark parallels with the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. Actor and activist,  "By blindly accepting the Government’s misguided invitation to sanction a discriminatory policy motivated by animosity toward a disfavored group, all in the name of a superficial claim of national security, the Court redeploys the same dangerous logic underlying Korematsu and merely replaces one “gravely wrong” decision with another."Although the Court's five majority justices disagreed with Justice Sotomayor, the majority opinion stated that the Court now had the opportunity to "express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—has no place in law under the Constitution.”The San Jose Day of Remembrance event was started 39 years ago by local activists to bring awareness of the United States government's actions to forcibly remove and disrupt the Japanese American community. The organizers, the

"By blindly accepting the Government’s misguided invitation to sanction a discriminatory policy motivated by animosity toward a disfavored group, all in the name of a superficial claim of national security, the Court redeploys the same dangerous logic underlying Korematsu and merely replaces one “gravely wrong” decision with another."Although the Court's five majority justices disagreed with Justice Sotomayor, the majority opinion stated that the Court now had the opportunity to "express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—has no place in law under the Constitution.”The San Jose Day of Remembrance event was started 39 years ago by local activists to bring awareness of the United States government's actions to forcibly remove and disrupt the Japanese American community. The organizers, the The

The

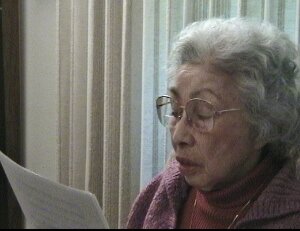

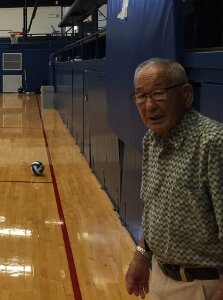

Jimi was a very caring person. This is also true about his wife, Eiko, and the rest of the Yamaichi family. Since Jimi's passing, I have heard numerous stories about how Jimi and Eiko took people under their wing, especially those that lost loved ones or individuals who were new to the community.I remember when I first met Jimi at my first Tule Lake Pilgrimage. I was new in the community and I didn't know anybody as I sat by myself in the auditorium. Jimi came by and sat next to me. He immediately struck up a conversation and gave me some historical items that he had collected. Jimi made me feel very special. Jimi did that with everyone.

Jimi was a very caring person. This is also true about his wife, Eiko, and the rest of the Yamaichi family. Since Jimi's passing, I have heard numerous stories about how Jimi and Eiko took people under their wing, especially those that lost loved ones or individuals who were new to the community.I remember when I first met Jimi at my first Tule Lake Pilgrimage. I was new in the community and I didn't know anybody as I sat by myself in the auditorium. Jimi came by and sat next to me. He immediately struck up a conversation and gave me some historical items that he had collected. Jimi made me feel very special. Jimi did that with everyone. I asked Jimi many questions about the

I asked Jimi many questions about the  One of my last memories of Jimi was at this year's

One of my last memories of Jimi was at this year's  On the day after his passing, it was somewhat difficult for me to give museum tours that day since I always have several Jimi stories that I incorporate into my narrative. I had to pause or slow down a bit after I became a bit emotional. I still get teary-eyed as I tell those stories but I also know that Jimi's spirit, vision, and dreams live on here at the Museum, in San Jose Japantown, at Tule Lake, and most importantly, within all of us.

On the day after his passing, it was somewhat difficult for me to give museum tours that day since I always have several Jimi stories that I incorporate into my narrative. I had to pause or slow down a bit after I became a bit emotional. I still get teary-eyed as I tell those stories but I also know that Jimi's spirit, vision, and dreams live on here at the Museum, in San Jose Japantown, at Tule Lake, and most importantly, within all of us.

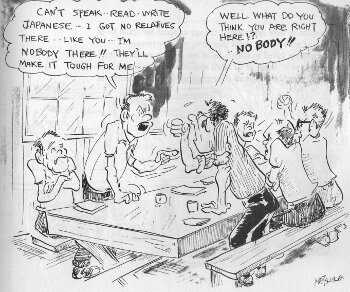

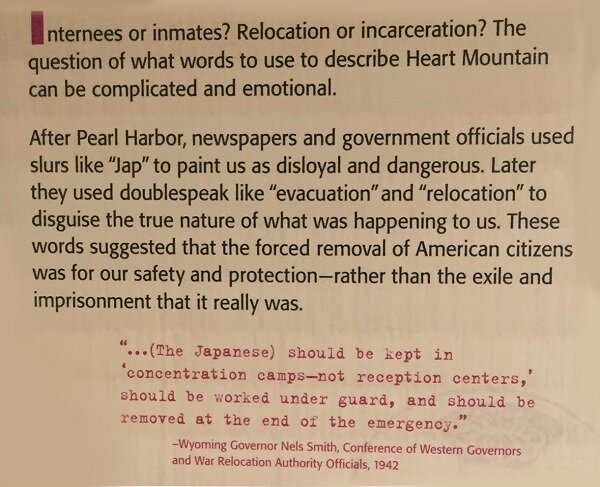

Phrasing and word usage are very important in shaping our attitudes about people, events, products, issues, and policies. For example, according to a CNBC 2013 poll, more people were opposed to President Obama's signature health care law when it was referred to as "Obamacare" rather than its official name, The Affordable Care Act. Similarly, in a 2017 IPSOS/NPR poll, more people felt that a particular tax should be abolished when it was referred to the "Death Tax" rather than the "Estate Tax," which were common terms used during policy discussions.In my

Phrasing and word usage are very important in shaping our attitudes about people, events, products, issues, and policies. For example, according to a CNBC 2013 poll, more people were opposed to President Obama's signature health care law when it was referred to as "Obamacare" rather than its official name, The Affordable Care Act. Similarly, in a 2017 IPSOS/NPR poll, more people felt that a particular tax should be abolished when it was referred to the "Death Tax" rather than the "Estate Tax," which were common terms used during policy discussions.In my

Additional information:

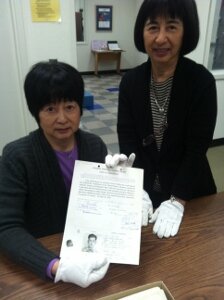

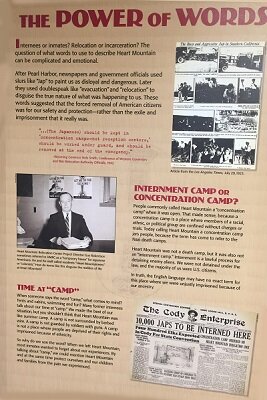

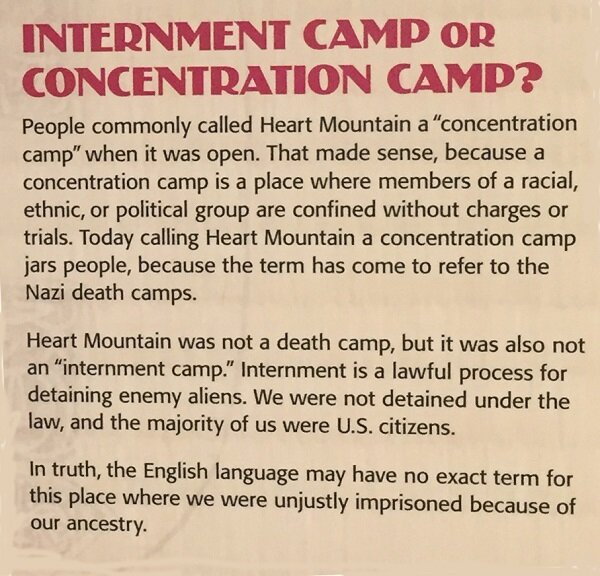

Additional information: By Will KakuThe Heart Mountain

By Will KakuThe Heart Mountain  Despite that significance in my family’s history, I could never find the time to make the journey to the

Despite that significance in my family’s history, I could never find the time to make the journey to the  The Heart Mountain Interpretative Center opened in 2011, just a year after we completed the major renovation of JAMsj. Because I assisted in providing content for the JAMsj camp exhibit, I was fully aware of space, cost, and vision constraints that had to be considered in exhibit design. I was keenly interested in how the

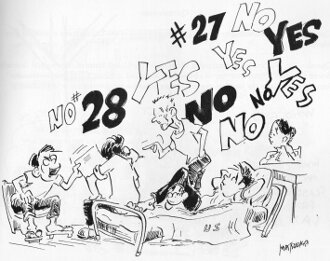

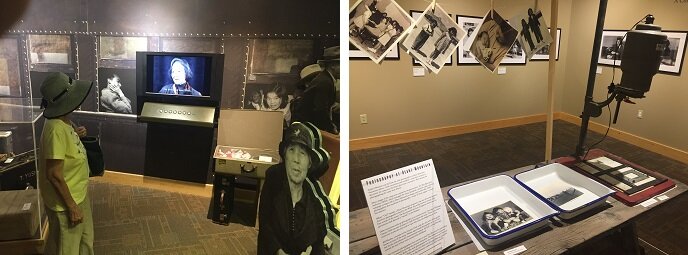

The Heart Mountain Interpretative Center opened in 2011, just a year after we completed the major renovation of JAMsj. Because I assisted in providing content for the JAMsj camp exhibit, I was fully aware of space, cost, and vision constraints that had to be considered in exhibit design. I was keenly interested in how the  One major aspect of the HWMF presentation, the first-person narrative, is extremely effective in bringing out an emotional connection to an infamous event in our nation’s history from over 75 years ago. After a short museum overview, my mom and I were encouraged to view the short film, All We Could Carry, by Oscar-winning filmmaker, Steven Okazaki. All We Could Carry powerfully captures the devastating impact of incarceration at Heart Mountain through the voices of former inmates.

One major aspect of the HWMF presentation, the first-person narrative, is extremely effective in bringing out an emotional connection to an infamous event in our nation’s history from over 75 years ago. After a short museum overview, my mom and I were encouraged to view the short film, All We Could Carry, by Oscar-winning filmmaker, Steven Okazaki. All We Could Carry powerfully captures the devastating impact of incarceration at Heart Mountain through the voices of former inmates.

Several kiosks in the museum also incorporate moving first-person accounts. Exhibit placards continuously reinforce the first-person point of view by utilizing the inclusive pronoun "we". We felt that we were also making our own journey through the great civil liberties and human rights tragedy from WW II.

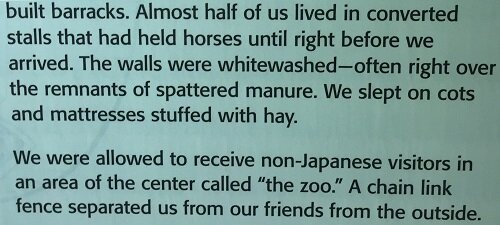

Several kiosks in the museum also incorporate moving first-person accounts. Exhibit placards continuously reinforce the first-person point of view by utilizing the inclusive pronoun "we". We felt that we were also making our own journey through the great civil liberties and human rights tragedy from WW II. The 11,000 square feet of space also enables exhibit images and artifacts to extend out into the floor space, providing a fully immersive experience to the visitor.

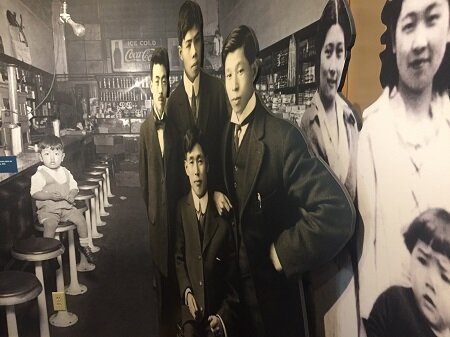

The 11,000 square feet of space also enables exhibit images and artifacts to extend out into the floor space, providing a fully immersive experience to the visitor. Every square foot of the museum is used to transport you back into the diverse and complex Japanese American incarceration experience. Even the reflective restroom toilet stalls convey the feeling of embarrassment and the loss of privacy that many former inmates experienced in the camps.

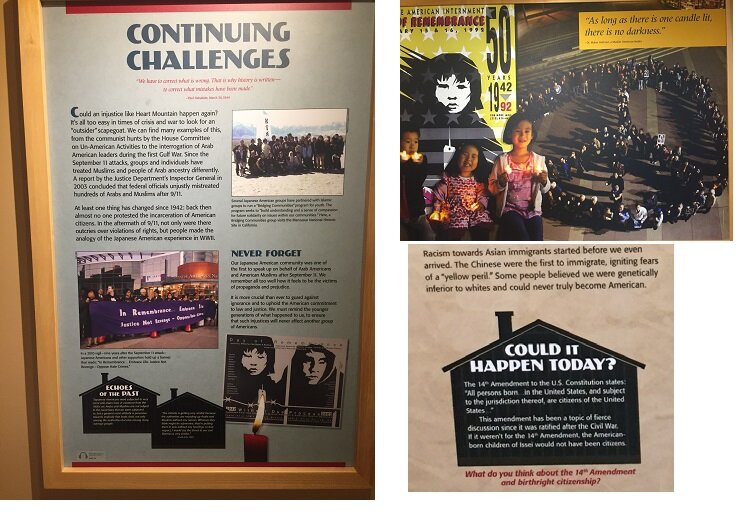

Every square foot of the museum is used to transport you back into the diverse and complex Japanese American incarceration experience. Even the reflective restroom toilet stalls convey the feeling of embarrassment and the loss of privacy that many former inmates experienced in the camps. Importantly, the museum exhibits challenge visitors with questions that are pertinent to our lives and political discourse today. One display asks us about what we think about the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship. Another asks us if there are any circumstances under which the curtailment of civil liberties by the government is justified.

Importantly, the museum exhibits challenge visitors with questions that are pertinent to our lives and political discourse today. One display asks us about what we think about the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship. Another asks us if there are any circumstances under which the curtailment of civil liberties by the government is justified. It took us a long time to explore the many museum displays and my mother became tired. We came back the next morning and wandered around the self-guided walking tour next to the museum. We saw the locations of the Heart Mountain hospital where my father worked for a short time, the school that he attended, and the train station where my father boarded a train that transferred him to the Tule Lake camp. We walked solemnly during that quiet, cool morning and we reflected on his life.

It took us a long time to explore the many museum displays and my mother became tired. We came back the next morning and wandered around the self-guided walking tour next to the museum. We saw the locations of the Heart Mountain hospital where my father worked for a short time, the school that he attended, and the train station where my father boarded a train that transferred him to the Tule Lake camp. We walked solemnly during that quiet, cool morning and we reflected on his life.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Related articles by Will Kaku:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Related articles by Will Kaku: