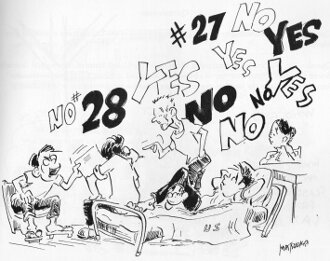

By Will KakuThe Heart Mountain concentration camp has always represented a critical turning point for my father’s family. As I had written in previous articles and speeches (links to some of these are below), Heart Mountain was the place where my father and his brothers struggled and debated as to how they were going to answer the infamous Questions 27 and 28. Heart Mountain was the location where my Uncle Tak decided that he was going to resist the draft. Heart Mountain was where my Aunt Itsu made a dramatic transformation from an innocent, acquiescent, and naive young women to one who became more aware of her dire situation and more vocal about racial discrimination and the violation of her civil rights.

By Will KakuThe Heart Mountain concentration camp has always represented a critical turning point for my father’s family. As I had written in previous articles and speeches (links to some of these are below), Heart Mountain was the place where my father and his brothers struggled and debated as to how they were going to answer the infamous Questions 27 and 28. Heart Mountain was the location where my Uncle Tak decided that he was going to resist the draft. Heart Mountain was where my Aunt Itsu made a dramatic transformation from an innocent, acquiescent, and naive young women to one who became more aware of her dire situation and more vocal about racial discrimination and the violation of her civil rights. Despite that significance in my family’s history, I could never find the time to make the journey to the Heart Mountain Interpretative Center. During the fall, my mother told me she wanted to visit Yellowstone National Park, so I decided that I could finally combine that trip with a visit to the old camp site which is just an hour drive from the park.

Despite that significance in my family’s history, I could never find the time to make the journey to the Heart Mountain Interpretative Center. During the fall, my mother told me she wanted to visit Yellowstone National Park, so I decided that I could finally combine that trip with a visit to the old camp site which is just an hour drive from the park. The Heart Mountain Interpretative Center opened in 2011, just a year after we completed the major renovation of JAMsj. Because I assisted in providing content for the JAMsj camp exhibit, I was fully aware of space, cost, and vision constraints that had to be considered in exhibit design. I was keenly interested in how the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation (HWMF) presented the Japanese American incarceration story to the public in their facility.

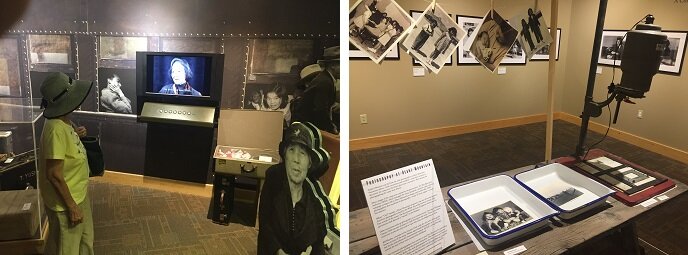

The Heart Mountain Interpretative Center opened in 2011, just a year after we completed the major renovation of JAMsj. Because I assisted in providing content for the JAMsj camp exhibit, I was fully aware of space, cost, and vision constraints that had to be considered in exhibit design. I was keenly interested in how the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation (HWMF) presented the Japanese American incarceration story to the public in their facility. One major aspect of the HWMF presentation, the first-person narrative, is extremely effective in bringing out an emotional connection to an infamous event in our nation’s history from over 75 years ago. After a short museum overview, my mom and I were encouraged to view the short film, All We Could Carry, by Oscar-winning filmmaker, Steven Okazaki. All We Could Carry powerfully captures the devastating impact of incarceration at Heart Mountain through the voices of former inmates.

One major aspect of the HWMF presentation, the first-person narrative, is extremely effective in bringing out an emotional connection to an infamous event in our nation’s history from over 75 years ago. After a short museum overview, my mom and I were encouraged to view the short film, All We Could Carry, by Oscar-winning filmmaker, Steven Okazaki. All We Could Carry powerfully captures the devastating impact of incarceration at Heart Mountain through the voices of former inmates.

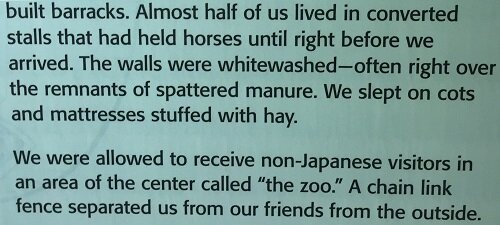

Several kiosks in the museum also incorporate moving first-person accounts. Exhibit placards continuously reinforce the first-person point of view by utilizing the inclusive pronoun "we". We felt that we were also making our own journey through the great civil liberties and human rights tragedy from WW II.

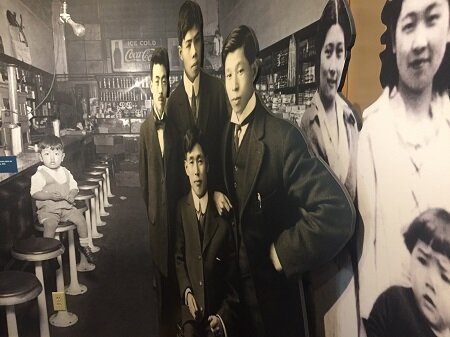

Several kiosks in the museum also incorporate moving first-person accounts. Exhibit placards continuously reinforce the first-person point of view by utilizing the inclusive pronoun "we". We felt that we were also making our own journey through the great civil liberties and human rights tragedy from WW II. The 11,000 square feet of space also enables exhibit images and artifacts to extend out into the floor space, providing a fully immersive experience to the visitor.

The 11,000 square feet of space also enables exhibit images and artifacts to extend out into the floor space, providing a fully immersive experience to the visitor. Every square foot of the museum is used to transport you back into the diverse and complex Japanese American incarceration experience. Even the reflective restroom toilet stalls convey the feeling of embarrassment and the loss of privacy that many former inmates experienced in the camps.

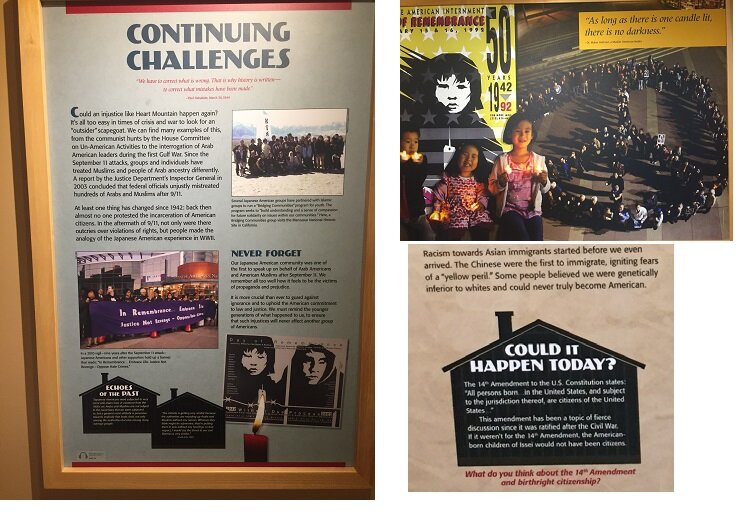

Every square foot of the museum is used to transport you back into the diverse and complex Japanese American incarceration experience. Even the reflective restroom toilet stalls convey the feeling of embarrassment and the loss of privacy that many former inmates experienced in the camps. Importantly, the museum exhibits challenge visitors with questions that are pertinent to our lives and political discourse today. One display asks us about what we think about the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship. Another asks us if there are any circumstances under which the curtailment of civil liberties by the government is justified.

Importantly, the museum exhibits challenge visitors with questions that are pertinent to our lives and political discourse today. One display asks us about what we think about the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship. Another asks us if there are any circumstances under which the curtailment of civil liberties by the government is justified. It took us a long time to explore the many museum displays and my mother became tired. We came back the next morning and wandered around the self-guided walking tour next to the museum. We saw the locations of the Heart Mountain hospital where my father worked for a short time, the school that he attended, and the train station where my father boarded a train that transferred him to the Tule Lake camp. We walked solemnly during that quiet, cool morning and we reflected on his life.

It took us a long time to explore the many museum displays and my mother became tired. We came back the next morning and wandered around the self-guided walking tour next to the museum. We saw the locations of the Heart Mountain hospital where my father worked for a short time, the school that he attended, and the train station where my father boarded a train that transferred him to the Tule Lake camp. We walked solemnly during that quiet, cool morning and we reflected on his life.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Related articles by Will Kaku:Lost WordsThe Secret of Tule LakeLiving HistoryPower of Words: Internment Camp or Concentration Camp

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Related articles by Will Kaku:Lost WordsThe Secret of Tule LakeLiving HistoryPower of Words: Internment Camp or Concentration Camp